Portrait by Susan Lapides

Urban Airspace Artist

It’s a metaphor for a way of being in the world, in that you need to be able to go in, share what you want to share, and leave without a trace. It's like going camping. It must have a light footprint.

By Heidi Legg

Tell us about the sky sculpture in Vancouver for the opening of the 30th Anniversary of the TED Talks.

I've been working on it for the last three years and it's hard to believe it's finally going to be real. It's the first test of my sculpture woven into the city at this scale. It's 745 feet. That's half of the main span of the Brooklyn Bridge. It's a huge jump in technical challenge, and it turns out that even for a soft net sculpture, when you increase the size the wind forces grow exponentially. My engineer told me, 'you've doubled the length of your sculpture but your wind forces are ten times larger.'

What materials do you use?

I'm using highly engineered fibers. One is called Spectra. It is fifteen times stronger than steel and we weave it into a twelve strand hollow grade being donated by Yale Cordage in Saco, Maine.

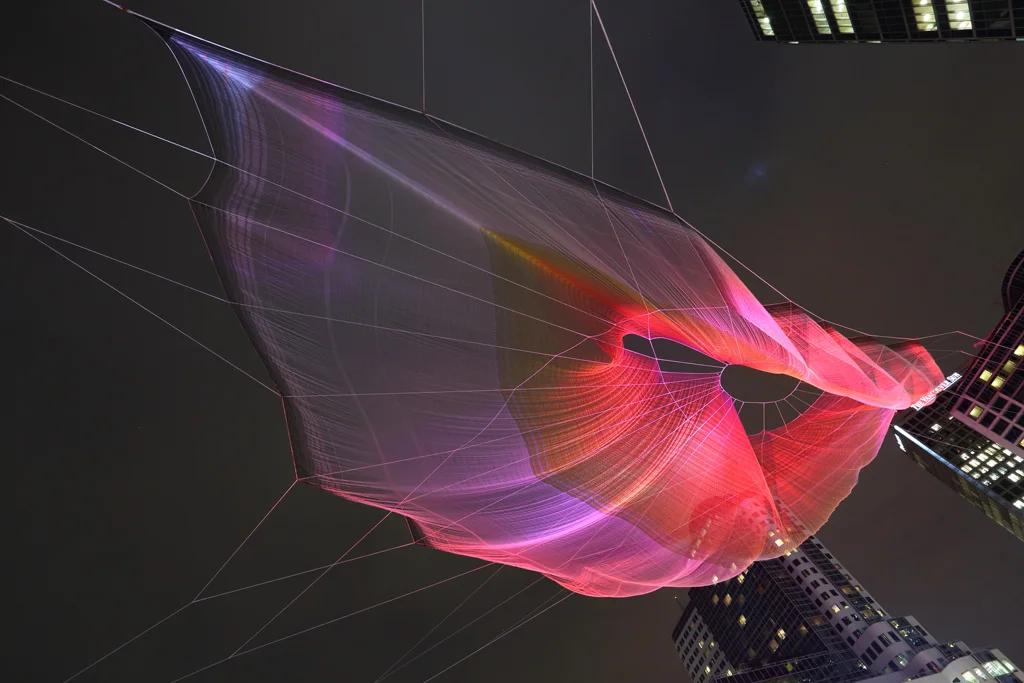

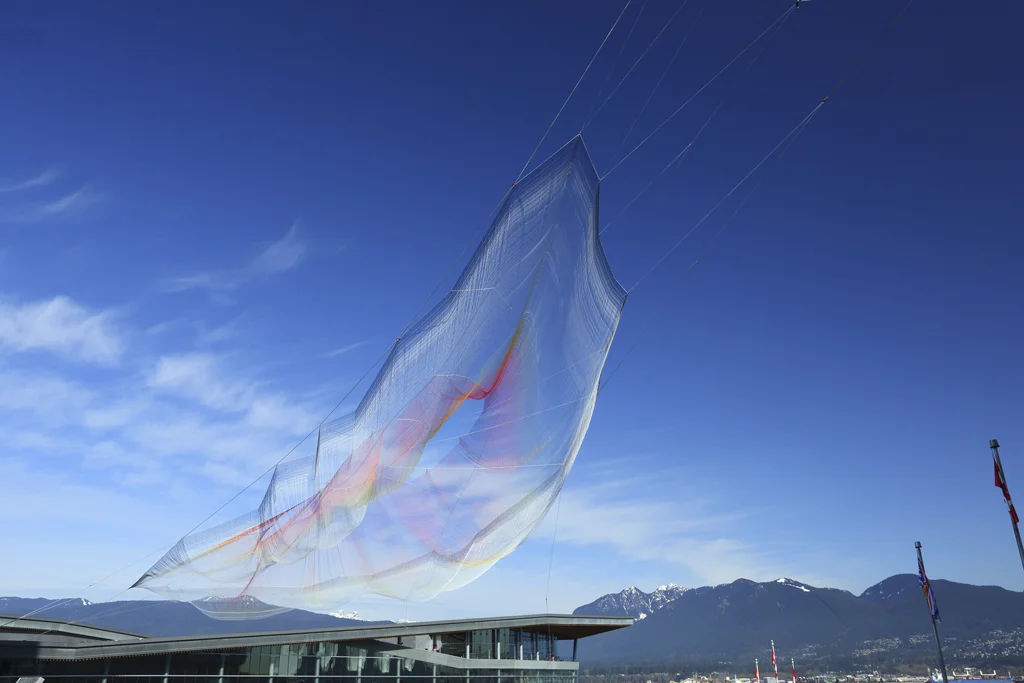

Skies Painted with Unnumbered Sparks, Vancouver 2014

How long will it be in Vancouver and where will it go next?

It was unveiled March 15th and it will stay up for a full week and two weekends. There are several cities working on plans to bring it to their city next.

Can you tell us who?

No. Major cities you know and love.

Aren’t your works usually up longer?

Yes. This is different. Most of my works that exist in the world are permanent commissions. The first major work is in Portugal, in Porto called She Changes; in the US, in downtown Phoenix - two city blocks - called Her Secret Is Patience; there is one at the San Francisco Airport called Every Beating Second.

Which has been up the longest?

The piece called She Changes in Porto, Portugal. Almost ten years.

How high is the Vancouver sculpture suspended?

We’re drilling into the roofs of major buildings, putting our steel structure in place. The piece is packed and getting ready to unfold on the ground. We're closing the street all night.

Skies Painted with Unnumbered Sparks, Vancouver 2014

How do you get permission to drill into buildings?

I ask very nicely. As they say with dating… it only takes one. Sometimes you have to ask more than one person.

Did you worry about permission from aviation regulators?

Canada aviation had to approve this. We had federal, provincial, and municipal hurdles to cross. For Vancouver, we have four different permits. We have a development permit, a building permit, a noise ordinance permit, and two road closure permits. The number of hurdles was daunting.

Did you need this kind of permission with your other structures?

Most of my work is permanent and that is a completely different entity. There are always multiple years in the development and when you design something with permanency in mind, it is done with great transparency. Every step is carefully developed and approved.

This work in Vancouver is designed to be agile and to travel as an idea from city to city. Therefore it needs to mobilize smoothly using only what already exists in the city, so it's a different endeavor. It's about being able to adapt and work with what's already on the site. We're attaching to the top of a twenty-four-storey Fairmont hotel and to the brand new Vancouver Convention Center with its giant grass roof.

It's a new model and it's the first test of my sculpture woven into the city in this way. The project that led up to this challenge was the 1.26 series, which was a real breakthrough.

Why was the 1.26 series a breakthrough for you?

It was the first completely soft sculpture that became so light it could tie into existing buildings with a structure made of these soft engineered fibers fifteen times stronger than steel. This new fiber enabled it to be so light that I can literally lace into the structure of the city, into existing buildings, and alight through air space lacing over streets and pedestrian plazas. That was a breakthrough. This discovery came through the pressure of wanting to do a project for the Biennial of the Americas, but the time was too short and there weren’t resources for a permanent structure or a steel armature, and I had to figure some new solution out on the fly. Through the kindness of donation of these special fibers from Yale Cordage, we were able to test a new idea – an urban sculpture at this softness at the scale of the city.

Where is the 1.26 series?

It premiered for the Biennial of the Americas in 2010 hosted in Denver, Colorado and then it traveled to Sydney, Australia and then to Amsterdam for its European premiere and it opened in Singapore March 7th. So I’ve had two exciting openings this month.

What do you consider as your big break as an artist?

I think my big break was the chance to build at the scale I envisioned, and that chance came from Europe in the form of an email. I literally received an email from an urban designer in Portugal saying they wanted a major public work - a permanent commission - to transform the waterfront at a new traffic roundabout. I actually thought it was a prank from my friends.

How did they know about you?

They had seen a temporary installation of mine in Madrid at an art fair called ARCO, which is the largest in Europe. I guess he looked me up online. His name is Manuel Sola Morales and he passed away recently, but he was an important urbanist who helped with the redesign of Barcelona's waterfront as well. He designed it together with the Pritzker Prize winner Rafael Moneo. I wrote back and he sent real pictures and I thought, 'oh my God, this is for real.' We installed December 2004. That was a huge break for me; that they trusted me to do it, I was shocked, but I lived up to it.

What did you do first?

I bought a ticket to Las Vegas to the trade fair of the industrial fabrics conference and I walked the aisles. My big brother came and met me so I wouldn't be alone in Las Vegas, and I found a fiber called Tenara, or its chemical name if you don't want to use that - that's the sort of brand name of what I use - it's called PTFE – polytetrafluoroethylene. It's basically the same thing as Teflon only made into a fiber. We take those with custom coloring and braid them and then knot them and create our structures.

When did you know you were onto something?

I did a temporary work on the underside of the interstate highway in Houston Texas, where the overpass broke up a beautiful running path along the bayou of this park. It was the first time the Texas Department of Transportation (DOT) would allow art. The DOT started calling me and telling me that people had always been afraid to go through that area and now they loved it. The realization came that putting a soft sculptural work in a place could transform a space and the way people felt about being in that space. Suddenly it's like the intentionality made it a different place and it even solved their safety issues.

What emotions do you think your soft structures evoke?

I think it comes from a memory of being a toddler holding onto my mother's legs, her skirt billowing above. It's this sense of being protected yet connected to open infinite space, and it's preverbal. That's why it's so hard to describe. It’s this deep human emotion that is at the core of all my work, and its scale is part of that sensation of being small and protected. It's not scale for its own end.

Skies Painted with Unnumbered Sparks, Vancouver 2014

When I see your work, I want to lie down on a grassy knoll.

In Phoenix, I got a call from my friend Alan who said that he’d received a call from a woman (I mentioned this story in my TED Talk) who’s never been interested in art, yet went into the office and grabbed everybody and had them lie down on the grass underneath the sculpture and just look up and watch the work moving with the changing currents of wind. I am beginning to discover now that while it starts from an individual desire, it awakens a social quality because you're sharing an experience with strangers that is real and has meaning. Suddenly, there's some third between you and a stranger that you're both sharing. I experienced it when I went to see Christo's Gates in Central Park and started talking to strangers about it. There's this ability to break down barriers in an authentic way. It’s a genuine shared experience in the city.

What artist has influenced you?

Working for Robert Rauschenberg. When I was twenty-two, I was living in a village in Bali and he was searching for someone in Asia to help coordinate his exhibitions there. I started helping him and was his personal guide because I spoke the languages in Indonesia and Malaysia.

I'd been there a few years by then after graduating from Harvard. I lived in Ubud, Bali and he asked to see pictures of my art, and then he asked to curate one of the first solo exhibitions of my work. I was making these batik canvasses and I had shown him pictures of them sort of flopping in the wind, but when I brought them to the exhibition, we framed them on stretchers. He made this comment that has reverberated for years to me. He encouraged me to return them to their original state, loose so that even the air currents in the gallery would interact with them and make them move. It's not like I went out and did that, but years later I thought back to this idea of returning them to the state when I was making them, and now that's what I do. It's about completely soft works that are soft enough to be influenced by the changing currents of wind. He was really a big influence conceptually on my work.

What inspires you when making your pieces?

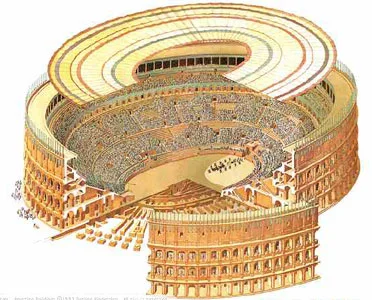

It always starts from the site, and that leads me to history and geography. I wanted to create something that could travel from city to city like an idea in visual form – TED is 'ideas worth spreading. I wanted a visual idea that could be shared from city to city. I was looking at history and social gatherings in history and looking back at what cities have done over thousands of years, and I had the privilege of going to the American Academy in Rome where I learned that the Colosseum in Rome had a monumental textile covering suspended from ropes above it called the Velarium. They know it existed because the holes for the masts that held it up in the stone still exist, and so my artistic process for this work was exploring what would be a Velarium for our time. Today, instead of gathering to watch violent spectacle, we gather to parlay ideas like the TED Conference, and how could I create a new kind of Velarium for our time? The title for the work is Skies Painted With Unnumbered Sparks.

Computer rendition of Velarium in Ancient Rome

I am using a computer software tool from Autodesk to model something with this complexity at this scale, draped with gravity and wind. I invited Aaron Koblin, who is a creative director at Google Creative Lab, whom I had met as a fellow speaker at TED to create the social interactivity that I imagined but could not create myself. He's been creating a new way that people can interact and literally paint the skies with lights using the mobile device in their pocket.

Collaboration is exciting because it reveals something I could not have imagined. Aaron is not only taking this beyond my skill set, but beyond what I could have imagined, and that kind of collaboration is very fulfilling.

I’m dying for more of that type of collaboration.

Aren’t we all? It's very rare. It's not about hiring someone. That's a different thing. This is someone with their own endeavor. I'm incredibly grateful to Aaron.

Yale Cordage also donated all the braiding and a foundation in Vancouver called the Burrard Arts Foundation has jumped in to help sponsor the cranes and the physical installation in Vancouver, along with the city of Vancouver. So many people are supporting this project.

What public opinion do you most want to change?

Assumptions of what a city should be or could be. We know what our urban centers are like today, but that doesn't have to be a status quo. We can re-envision them to be different. We know that the physical space we're surrounded by affects how we feel emotionally every day of our lives, right? Not only does research show it but you know from personal experience that when you're apartment shopping and you look at one that's flooded with light and one that is dark and in the basement, that you don't want to live in the one in the basement. We know that physical spaces affect our emotions and who we are in our behavior. I believe we can shape our cities in new ways and we're showing it in this piece. Overnight a soft 745-foot sculpture form is changing a particular place for a moment.

Where do you get your news?

I'm a New York Times junkie. Online. I read The Economist and The New Yorker in print, and I'm glued to the New York Times online.

Date you're most looking forward to?

March 17th is my TED Talk and the entire audience is being invited to come outside underneath the sculpture to spend time and interact with the sculpture, and that's the opening night of the 30th anniversary. I'm excited to return to TED because there's no [other] experience where within five minutes I have conversations about my sculpture with Al Gore, Jason Mraz, and General McChrystal.

Do you have any Secret Source?

Yes, my husband, David Feldman, who is the most important collaborator in my work in its conceptual development, solving challenges and setting out goals. Sometimes I wouldn’t think that I could achieve something, I wouldn't even consider it a possibility, and he helps me think what the work can do. He can look at a sketch and say, 'you know what? You can do better' and I say, 'you're right' and I go back to the drawing board. Not everyone can say that to you and he can, and I trust him. I'm terrified of what's coming up. But David mentioned that unlike performers, most of my creative work is done in advance. So, by the time it's opening night, the work is done.