Portrait by Alan Savenor in front of the "Trays", an iconic venue at the Harvard GSD

Architect

Ibañez Kim

Harvard Graduate School of Design

"We have crazy ideas all the time as architects… couldn't we have these shelters that are packed really tight and you hydrate them and then they blow up and suddenly they become some type of tent?"

by Heidi Legg

Born and educated in Buenos Aires, Mariana Ibañez has been teaching at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD) for 10 years after working closely in London with globally-celebrated Zaha Hadid, her mentor, who passed away this winter leaving the world her iconic structures. Today, Ibañez and her partner Simon Kim have their own closely watched firm called Ibañez Kim where they experiment each year in a different city with a construct that explores the relationship between urbanism and how we move through the city. They also have a lab called Immersive Kinematics where they do much of their research and prototyping. We sat down with Ibañez to discuss how she sees the role of architects in a world in which some are in dire need for basic housing, while others have a responsibility to experiment with technology and push the envelope. Her insights into biomimetics and the crossover of disciplines from robotics to material science to artificial intelligence is a long way from a Staedtler Mars pencil.

Do you see the world on the cusp of something new in architecture?

More so than ever, as the possibilities of technology transforming the built environment and architecture are incredible. It has always been the case in terms of new materials and how we put buildings together, but I think we're now closer to something else where our buildings can become active and reactive and become more immersive experiences. I see how media and other technologies, like sensors and adaptive materials, might become part of our everyday life and be incorporated in our everyday spaces. The relationship between the advancements in technology and architecture are really producing a very significant transformation in the types of buildings that we can imagine and therefore the spaces that we end up inhabiting.

APoC courtesy of Ibañez Kim

What is a 'responsive environment?'

A responsive environment can be interpreted in multiple ways using synonyms related to adaptation and interaction. Imagine the way you interact with your phone. Imagine if you could do that with your spaces, with your walls, and with the environmental conditions. The ‘Internet of Things’ also plays a big role in these ideas in which the materials change from something inert, to something that can be transformed. Materials can compute and communicate with everything around you – everything that has the capacity to exchange data can transform it into something else.

What will be responsive and how exactly will we see it work?

I definitely see from energy use and management all the way to J.G. Ballard's science fiction stories where immersive environments have some form of psychotropic properties. For a very long time, the idea of intelligent buildings has been prescient. From occupation patterns to programmatic adaptability, buildings are to a certain degree already active and responsive. Sometimes it gets done if there's enough budget and sometimes it doesn't.

I don’t think it's only about problem solving. I think it's about 'the life of buildings' where buildings will become active agents in the city as another type of inhabitant.

MoMA PS1: Mechanical Garden courtesy of Ibañez Kim

Are you suggesting this will happen in a robotic way?

Definitely. I think there are multiple fields that can produce this: from robotics, to augmented reality, to artificial intelligence, to computer science, to material science, and architecture. All of these fields, to a certain degree, are about design and designing systems. It is in the dialogue between those disciplines and the advancements of each one separately that a new built environment can be imagined.

It's very interesting, in that regard, to look at the history of architecture. It was really architects who have always been preoccupied with the built environment, but now you can see that Facebook is doing experiments with spaces, Apple is doing experiments with spaces, computer scientists and people interested in the world of robotics and artificial intelligence are dealing with space. In a sense, they're going into the realm of architecture, and at the same time, architects are looking into some of those developments and rethinking them in the context of space making.

Would you give us an example?

Materiality like responsive walls would be an example. Instead of thinking that a wall is a bunch of bricks laid on top of one another…a wall is something that can change in depth, in transparency, in porosity. Suddenly walls can become navigation systems. Imagine the implications for an airport with way-finding devices that at the same time could become form-making. Look at the popularity of the shared economy: What if the space can grow and shrink according to need, and that type of transformation is considered when the design is produced.

The house actually grows?

Why not?

How does a house grow?

With kinetics and mechanical engineering, for example. The advancements in the field of material science has been so incredible in the past few years, for example in the field of biomimetics. (Wikipedia: Biomimetics or biomimicry is the imitation of the models, systems, and elements of nature for the purpose of solving complex human problems.)

The relationship between biomimetics and design is very interesting. Many organisms have the capacity to produce light or energy and there's a way in which we can transform energy into heat. Many people in my field are interested in learning from those processes and trying to find ways to create that in a synthetic manner. This idea of synthetic nature that is adapted to produce spaces for us as inhabitants is something that is very current in development.

Conic Assemblies courtesy of Ibañez Kim

So it’s architectural material inspired by nature?

Inspiration and knowledge. Some people are doing things that look like nature. Other people are interested in things that behave like nature. In architecture, particularly at the scale in which we operate, it's not such a literal translation. It's about understanding what kind of technologies could produce those conditions and understanding the architectural and spatial implications of applying that research into full-scale buildings. A lot is happening at the scale of the devices and at the scale of installations in museums or in fairly small pieces. I don't think that model has yet scaled. It has not been proven how that scaling up occurs.

Today, we have some very sophisticated buildings in terms of their relationships to climatic conditions, energy and light. But this type of development is only the beginning in understanding the type of intelligence that our buildings should have in terms of being part of an environment. We are not static. Our context is constantly adapting. Shouldn't our spaces be able to do the same? The way I think about it is that we are imbedded within a dynamic condition. How can our buildings participate into that dynamism?

Are traditional urban building codes hindering progress and change in this area?

Buildings are complex and I think what your question touched on is very important: even though we can clearly identify buildings as objects, they're not completely autonomous. For the most part, they're in cities and that means they're interacting with other buildings and with streets and transportation, but they are also interacting with people. The building code is not something fixed either. It takes time, but it changes.

Architecture is a slow profession. I am hopeful that, as we see the advantages of revising certain very well-established ideas, some assumed to be permanent, some of these things will slowly begin to change. It will be better for the environment and it will be better for us as users, and effectively that has to be a good thing.

I’ve heard you speak of an ‘adaptive structure.’ What is this?

It is something that has the capacity to transform. Whether that transformation is done through kinetics or whether it is about perception. It is the capacity to adapt, the capacity to evolve.

Does the structure have to have its own artificial intelligence (AI) to do this?

I like to think that spaces could learn from experience, from patterns of use. They could respond to unexpected changes in the environment or new forms of input. Imagine a space that could have memory and what could that mean and how that memory would be registered. Would it be important for us to understand that there's memory or will something happen that you don't know about, like what's happening inside your body at all times? That way of understanding the built environment can develop enormously once our idea around intelligent buildings goes beyond having an HVAC system that spends less energy.

The Minister @ Play Day courtesy of Ibañez Kim

When we first met you mentioned that adaptive structures could help with the current refugee and migration issues. How?

I think architects have the capacity and the tools to be more instrumental in helping with this type of situation. Many architects already dedicate their lives and careers to think about issues related to disaster relief, fast deployment of shelters, or anticipatory design for underserved communities. I think there's a version of it that is related to crisis and there's another aspect of it that is related to urgency.

In situations that are urgent, you usually work with technology that is at hand and try to be very fast in response. At the same time, there is a lot of research that can happen that in the future will be even more effective and more sustainable at assisting in these situations. We have crazy ideas all the time as architects… couldn't we have these shelters that are packed really tight and you hydrate them and then they blow up and suddenly they become some type of tent? Think of the way sponges work: can we pack these things so tightly such that you could send hundreds of thousands at once?

Do you teach to this?

At the GSD, one will find a lot of lines of inquiry that exist or coexist at all times. We have programs that focus on architectural activism, disaster relief and anticipatory practice and, at the same time, we have other tracks that are focussing on technology. Sometimes they cross over and sometimes they don't. We're dealing simultaneously with problems that are historically central to the design discipline and with things that are very much of the now and with a projection into the future. We have projects that are very pragmatic and about very practical issues and at the same time the most fantastic ideas.

Apple, Google and Facebook have designed campuses in California. Have they pushed the envelope far enough?

I think it's very easy from the outside to say that the envelope can always be pushed further. You'll always think, ‘Oh, if you come and ask me to do the Google campus, this is what I would do.’

I agree that some of the risks that these companies might take within their R & D labs when thinking about their new product lines might be pushing the envelope more. But I also think these companies have a genuine interest to be engaged in aspects that affect space making, as I said before, and to understand what that could be. At some point you need to deal with the realities of building something now.

I know many of the firms in charge of some of those projects very well, and I think for the most part these are people who have been leaders in innovation. I trust that they are trying to be in dialogue with very creative minds and people who have a lot of experience building at that scale. As I said, we can always push the envelope more and I hope that some of those projects are at least capable of planting seeds that will lead to greater change.

So you think we should be looking at these new technology buildings on the West coast for new shoots? New ideas emerging?

I think they are discussing things that are visible and others are not. From materials to experience: how people work, how people interact in a work space, how can space support productivity. And these questions come hand in hand with things like new policies for maternity leave and work schedules. Do we still need a 9-5 thing or is it better to let people work when they're the most productive? I think it is about understanding lifestyle in relationship to work. We saw this early on in Boston in forward thinking campuses.

RolyPolygon. Confessional courtesy of Ibañez Kim

You think this work/life merging style began in Boston?

The MIT Media Lab, to a certain degree, had a lot to do with some of those ideas. People were having incredibly productive conversations in lounge space or unstructured spaces. That's why all the images you see have a red couch in a lounge with a young Millennial working on an Apple device. For quite some time, that image represented the spaces where ideas about the new world will emerge.

I think we're past that model, but I think that really transformed the corporate world and corporate structure in how offices were laid out and the idea of what a flexible plan was and so on and so forth. I see that new seeds of new ideas might emerge from some of the new campus buildings that we're seeing emerge today on the West Coast.

Where else do you see adaptive structures happening?

The U.S. is fairly conservative when it comes to architecture, not necessarily what happens inside academic institutions, but what gets built tends to be conservative. In terms of experiments in city-making, there are many things to look at in China. They make new cities in a very short period of time, for better or worse. The design models they use are very different.

Where else are exciting things happening in architecture?

I was definitely very excited about what was happening in London when I was there. One of the things I still enjoy and find productive is working with global teams. Even if I was working from London, our engineers many times were in the U.S. and we were working with a specialist in environmental conditions from Canada and developers from Asia. There are ideas everywhere.

This spring, your mentor, Zaha Hadid, passed away. How would you describe her influence on you?

Zaha... she was our mentor, guide, teacher and an amazing friend. We met whenever we could to share stories and ask advice. Her loss, obviously, is enormous for us, as well as in terms of her architectural influence. I started looking at her work when I was an undergraduate and it's an incredible feat. I think she transformed the world. Her work will always be something that we aspire to continue as her legacy and her ideas and her lessons.

She defined everything from how we view the world to how we build the world. She created spaces that people only dared to imagine before her time. She was questioned every step of the way. She was told that her visions were impossible and she was always proud to say that she proved everybody wrong. She left a legacy that is as much discursive and important for us as architects as it is for the world.

If you look at the work that she was engaged with throughout her practice, she was always pushing the boundaries of what could be done. It is hard to describe with words the enormous void and sadness we feel.

What were your favorites?

I was very involved with the London Aquatic Center, the pools for the Olympic Games in 2012. It was an incredible project of which to be part.

I love her early work. I always have this wish that I had been in her office when they were still doing the collective paintings. That's how her ideas were first shared with the world. When I started working with her, the office was still a fairly small compared to the huge operation of today. I think I was employee number 50 and now there are 400. I was very lucky to be able to work directly with her and with Patrik, her partner and director of the office.

I think they're doing incredible things with beautiful skyscrapers and really redefining what a tower could be, but equally, I think the institutional work that they've done is quite amazing, not only because of its physical beauty but in how they redefine how we use space. If you look at the layout of the BMW factory she designed, the fact that the production line and the workers are mixed in the same space, it is as though they're part of some fluid exchange.

I have always been interested in social conditions and how a building has the capacity to construct that. Equally, I am very interested in how buildings relate to the city. Zaha saw this as a fluid exchange between the public realm and the interior spaces of buildings and I think that fluidity is something that produced a great deal of work.

Why should society care about architecture?

I am so happy you ask that question. I think that society for the most part doesn't value architecture as much as it should. Look around. We are in architecture within architecture and next to architecture. We spend most of our lives connected to architecture and I believe that whatever we design has the capacity to transform how we live. A good space can have such a big influence on your mood, your productivity, and your disposition towards life and how your senses react to your space. How could we think about anything else?

What public opinion would you want to change?

I would like the general public to be more open towards experimentation in space making and architecture. There's a lot of stylization in architecture. I mean the fact that people are still building houses today that look from the Victorian period or whatever time period…I can't make sense of that. I think it is tragic. There's a way in which we have embraced advancements in every aspect of our lives from medicine to the way we communicate and people still see the places they inhabit as something that is detached from that world.

Could it be that the history of a style of design is comforting?

A new space doesn't need to be cold or what people associate with the ideas of modernism, which I understand aesthetically doesn't fit everybody's taste. It goes beyond the issues of taste and style. It goes to a more fundamental understanding of the way we live. I see people adapting to spaces that are not a reflection of how we live today. I would like a general audience that is more open to new ideas and with an understanding about how much influence that can have in their everyday lives.

There's a tension nowadays between this new urban and people yearning for simpler structures in the middle of the woods. How are these tensions reconciled? How does architecture respond to the needs of both sides?

Much of the conversation that we're having right now applies to only one part of the world. Other parts of the world have more urgent things to deal with, but at the same time, I think we are responsible as a society for thinking about the future. I read a very interesting article this week about how people are trying very hard to find spaces where they don't have to be connected and trying to recover some of the privacy and down time that we used to have before. I think space could have quite a critical role in establishing those connections or those barriers.

Architecture is constantly negotiating between those things. The types of things that people normally associate with warmth or comfort or a sense of belonging and something that is known, I think that still exists in contemporary spaces.

Architects are trying to understand how to participate or be in dialogue with the environment and constantly trying to advance that question. At the same time as people are craving some form of return to nature, more people are moving to urban areas and cities are becoming denser. There's definitely this question on the table on how to get away with both worlds: the questions of densification and the opposite of urbanization and we're testing ideas. It’s definitely a question that I see on the minds of everybody from students to practicing architects and I'm talking about more than gardens. It's about a different way of understanding life cycles, and the way we inhabit spaces and how we structure our life in relationship to our spaces.

Step 7: Our Fathers courtesy of Ibañez Kim

You co-founded Ibanez Kim with your husband in 2005. How do you make a personal/work relationship work?

Maybe it's true for other professions but the life of an architect is a very particular life and I think if you can find somebody that is likeminded and passionate and is interested in the same things, it's very easy to be partners in life and partners in work. I think it's a fairly common thing in architecture. I can't imagine something else.

What is your current obsession in your work projects?

This is a very interesting moment for us. Our practice is expanding. We have a number of very architectural projects. We're doing a housing project in Buenos Aires. We're doing a couple of small projects in the Boston/Wellesley/Cambridge area that are all medium-size institutional and commercial spaces and at the same time we continue with our very experimental inquiry.

We're constantly doing competitions. Sometimes projects are very abstract or they can be about imagining buildings and we also have an ongoing research on the relationship between architecture and urbanism.

For the past four years you have been known to create an urban project. Can you tell us about it?

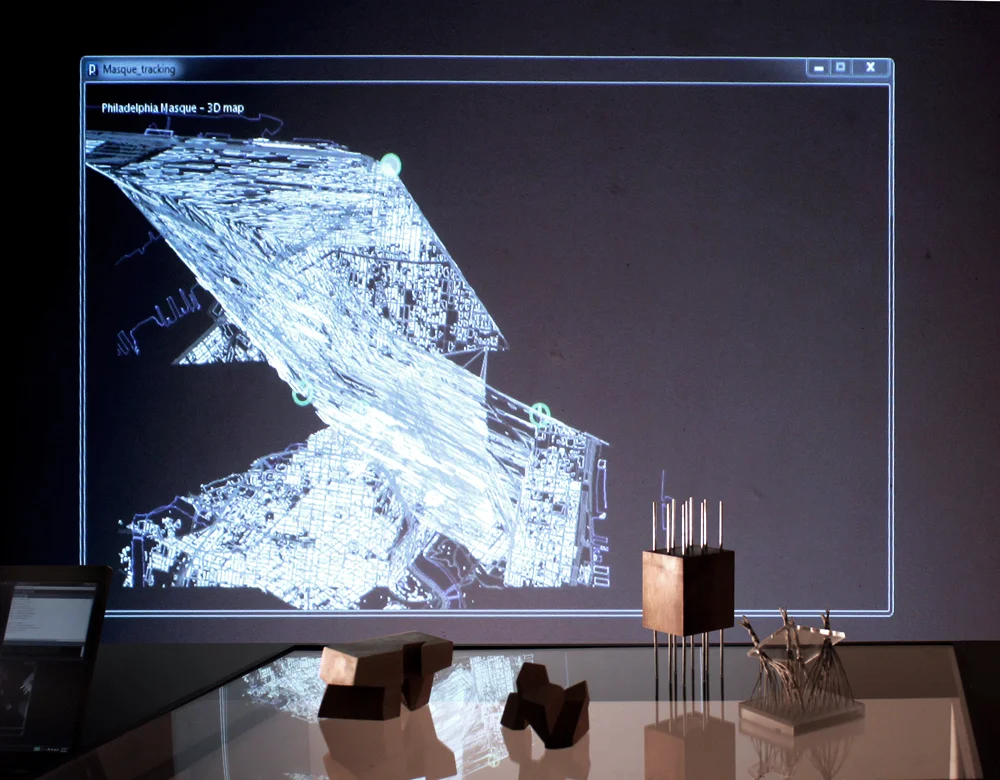

Every year we select a city or a number of cities and we do experimental projects for each one. We have one for Philadelphia, one for D.C. and one that combines Tokyo, Paris and London this year, our fourth year.

Our office is still fairly small and during the summers it grows substantially. It grows and shrinks according to the volume of work and the time of the year. This week we have about five new people joining. They get distributed into the firm projects. Simon and I initiate all the projects and usually one of us is the lead and the other functions more as a critic or as a consultant for that project and then we discuss and sometimes we do projects together. We like designing together. We fight a lot for the right reasons to determine if we feel it's still worth doing it. It goes back and forth. It's a fairly fluid structure.

Would you let us in on one of this year’s experimental projects?

The one in Philadelphia is actually done. It's called the Philadelphia Mask and we also finished the one in D.C. They're all about opportunities to connect architecture with new forms of urbanism and about how we think about the connection between public space and private space, and about using new technologies.

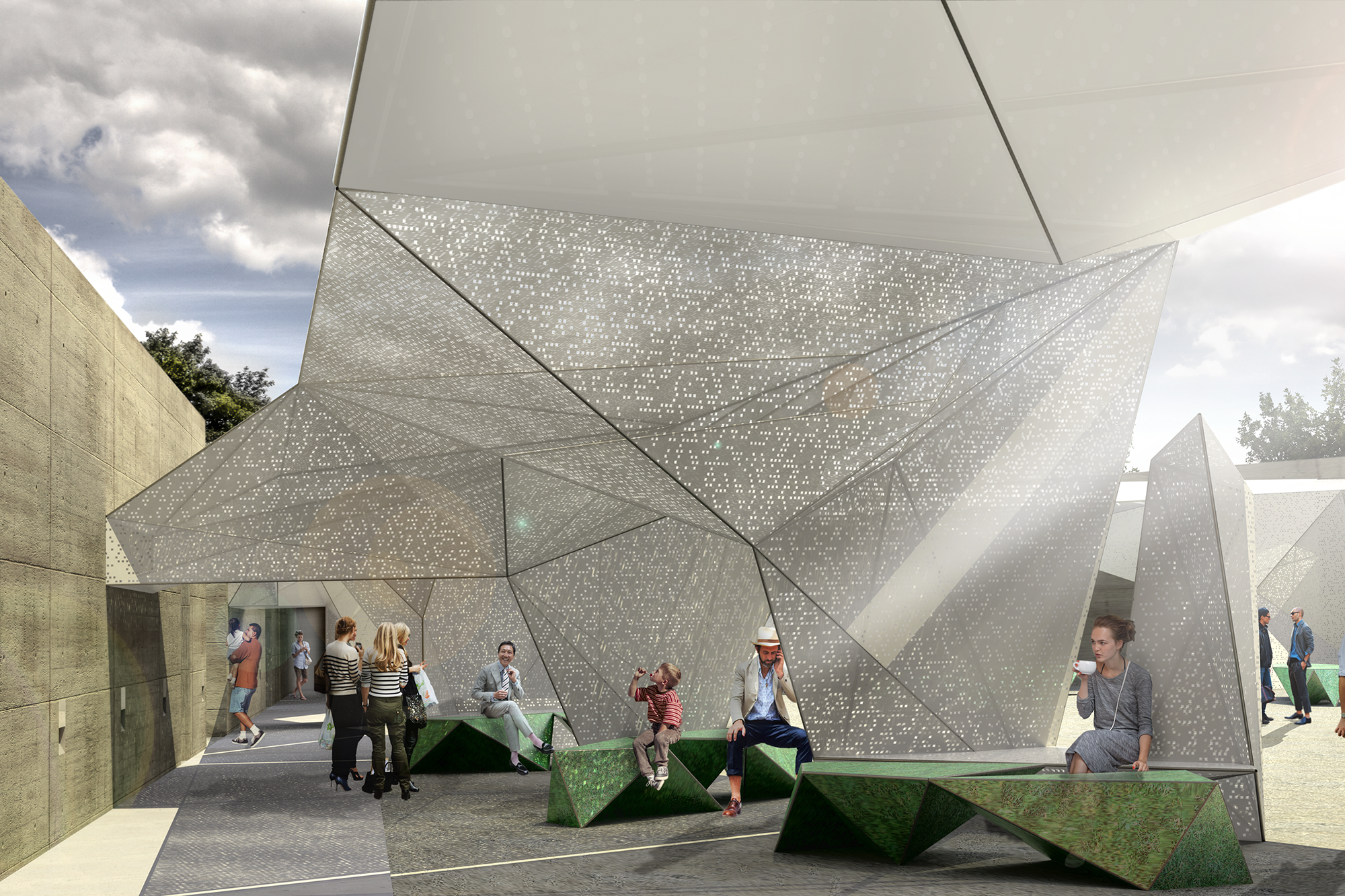

Philadelphia Masque by Ibañez Kim

The one in Philadelphia was super fun because we did these pavilions that were supposed to alter how you cognitively understand the city and each one of the pavilions had a material characteristic and a behavior associated with it. Some were linear, straight, and crystalline but also some were kinetic and related to the management of light or sound and they engaged with people in different ways. It’s architecture as place makers to contribute to how we understand the city and how we move through it. We're very interested in that type of fluidity.

Have you chosen your next city for next year?

We are working on a project that is a spin on 'Powers of 10' – a project done by Charles and Ray Eames many years ago.

What city will you choose?

Most likely New York. It’s interesting because we’ve been purposefully staying away from it. I think New York is par excellence the city where everybody experiments. It has been a laboratory for ideas for every single architect. So we've been purposefully staying away from it but ‘Powers’ can only happen in New York as a starting point. So we will see how we deal with it.

Where do you go locally to get inspired?

I love the Carpenter Center by Corbusier. I think it's an incredible space. I also love the Saarinen Chapel at MIT. Those are my two go-to buildings.

When drafting, do you have a favorite pencil or software?

I do everything on my computer, now. I sketch a lot, but I sketch in the computer. I haven't sketched by hand in a while.

What do you use for sketching?

Rhino and Maya.

What do you bring back here from Buenos Aires?

Yerba Mate tea.

Where should I go in Buenos Aires if I were to visit?

Banco de Londres by Clorinda Testa is an amazing piece of architecture and my country house, an hour outside of the city.

What do Argentineans love most about America?

Opportunity. I know maybe this sounds weird at this time, but political stability. I think that is very easily taken for granted, quite quickly.

What else? The mix of people in Cambridge. I love the heterogeneity at least in the city where we live and that's also something that I loved about living in Europe.

What is your news source?

Everything online: Flipboard, Facebook and all the million links that come through those platforms. I read The New York Times. I like reading about science and technology, and I read a lot about architecture from news outlets like the Dezeen or Archinect, Architizer.

We're looking forward to seeing what you come up with next.

Thank you.