Portrait by Melora Myslik Balson

Founder, Inner City Weightlifting (ICW)

A Restart for Youth in Urban Gangs

It’s true inclusion –which doesn't only disrupt the system for our students but disrupts the system for future generations.

By Heidi Legg

Last week, 56 members of the MS-13 Boston gang were indicted on charges of murder, drug trafficking and other crimes. In a city of extreme wealth and livability, where education is prized, people wonder how these young kids land on the street and what can be done to help them. Some write the problem off as dangerous and not their issue and one to simply stay away from. The chasm is one played out across many major US cities. Income inequality and opportunity are being touted loudly in the current Presidential primary season. We sat down with Jon Feinman, the founder of Inner City Weightlifting (ICW), who five years ago decided to actually do something about it. Today he trains young former gang members in his gym into a mainstream where they can finally have access. He brings in high-net worth people who want to be both trained physically and make a difference. It’s the great collide.

People say it takes five years to start a business or, in your case, a non-profit. How are you feeling five years in?

We've been really fortunate. We grew from a $75,000 organization our first year, then $250,000, then $545,000, $750,000 and then last year over $1 million for the first time.

We started with four students and now we have over 150 students and a few dedicated facilities. We've been fortunate to have this kind of growth and to have this amazing support network. Each year, as we grow, the set of challenges change. To me, that's the best sign.

Our big challenge now is figuring out how we scale the model beyond the few people that are working on it. It's an exciting time.

If you succeed wildly, how will the world around us be different?

The first year was all about, ‘can we actually engage this population?' These gang members [or kids at risk of joining gangs] were coming into the gym through students who would bring their friends. It was going so well we outgrew the initial gym. Then the second year was really about, 'can we actually get our students certified as trainers? Can they actually have a meaningful career as a trainer and would anyone want to train with them?' Here we are five years later, and we've over 300 clients.

Now it's really about whether we can create this more systemic change: We can create hope, we can create more opportunities and new networks, but can we now purposely overlap that in such a way that we disrupt the whole system that leads kids to the streets in the first place?

What are you noticing so far?

One of the things that's amazing to me is when you look at these major cities that are affected by gang violence, they all have this contrast – these areas that are extremely affluent and, within a block, an area where people are told, 'don't cross the street. Don't go to that part of the city.' It hit home.

Then I look at what's happening in our gyms every day. We've got partners from VC firms inviting our students into their homes for dinner. Students who have been shot before or who have done years in jail and on Boston's pack list, which is a list the police have of people identified as gang leaders, merging with these networks so that an area of the city that's extremely affluent bumps right into an area of the city that has a lot of violence. This allows us to create these networks that merge so that children growing up on the ‘other side of the street’ have the same opportunity. There will always be these disparities of income, that’s just the way it is. The more concerning part is the fact that there's such a disparity in networks and opportunity.

With understanding we can remove the stigma that keeps certain communities segregated and isolated and also engage a demographic of people who care and want to do something to help. It can be as simple as an invitation into someone's home for dinner. It can be paying for one of our student's kids to go to summer camp with their kids. With these little things, how does the world look different? Rather than having these big, diverse cities that are incredibly segregated, now we have inclusive diversity. We have inclusive cities.

How do you help people overcome fear and the stigma regarding this population?

Through understanding. I look at everything that's happening. I'm not from Baltimore. I'm not from Ferguson. I can't personally understand what's happening in those cities that affect the people that live there, but I do hear the conversation that's happening around those cities. From what we've seen people are really quick to form their own conclusions and they're not as quick to understand why people are engaged in a behavior. What happens in the gym is that people start to understand why. They start to see each other for who they are, and not for the decisions that might get put on the news.

It’s true inclusion, which doesn't only disrupt the system for our students but disrupts the system for future generations, and can theoretically disrupt it altogether so that we're not even talking about widespread coordinated youth violence. There's always going to be one off violence but gang violence forms for a very different set of reasons.

What does this look like in a training session?

By working side by side with the student for an hour-long weight training session, at some point you're going to be talking together and all of a sudden you're going to see how much people have in common rather than what separates them.

I think the biggest realization is that when people know each other and they understand each other, it's okay to disagree and that disagreement can manifest itself in meaningful conversation rather than a harmful stereotype that protects whatever it is you're trying to protect. Overcoming fear is not rocket science. But it's incredibly difficult to execute. We do it by creating understanding.

Why were you personally motivated to fix this?

It goes back to a year of AmeriCorps I did in 2005, where I worked with a group of young people in a gang called MS13 and everyone told me, 'don't go near them. They're too dangerous. They're never going to turn their lives around. Don't waste your time.'

They're an international gang in LA, El Salvador, and all throughout Central America and this country as well, and they and 18th Street are two of the most dangerous gangs out there.

The more I got to know them, the more I saw how segregated and isolated they were, and not just in the obvious form, but in this more subtle form: they don’t have access to networks that can make them aware of what opportunities are out there, or connect them with the opportunities even if they were aware of them. Secondly, there was a real confusion between lack of care and lack of hope. People thought these kids didn't care. But they care so much that they're willing to lose their life to a bullet or jail to protect what little they have.

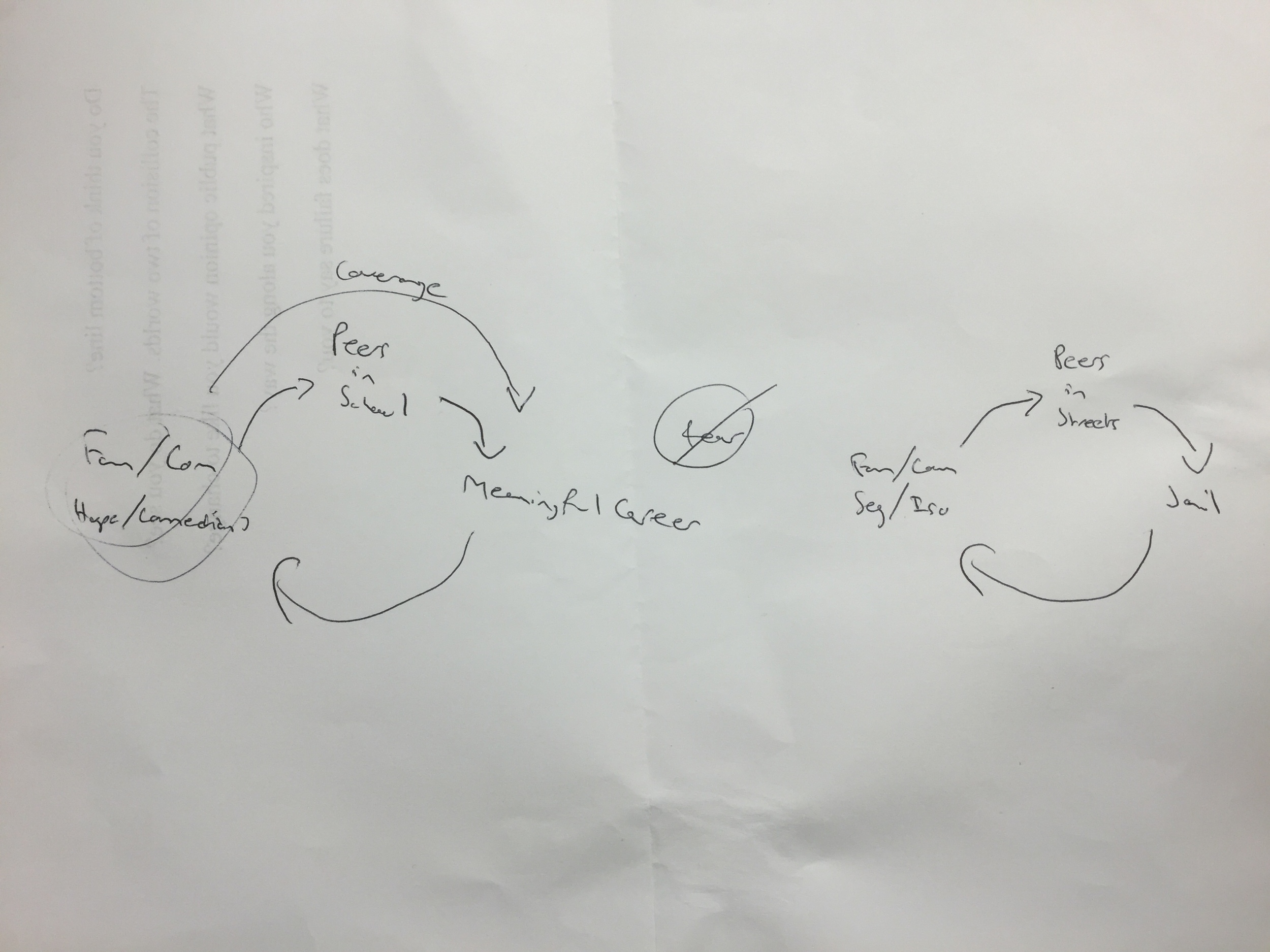

What they lacked was hope for an alternate path. The truth is no one wants to be dead or in jail but there's a set of circumstances that leads our students to this path that manifests itself in the streets in violence. From the work we've done over the last five years, we actually started to see the system that's driving it. If we look at the typical person born in America, they're born into a family and community with hope, connections, and opportunity. You join your friends in school and then go from school to finding a meaningful career. Then you start your own family with the same hope, connections and opportunity and what allows for this to happen is the fact that you have this circle.

Your family is covering you. You don't have to worry about food, shelter, or what's going to happen the next day. Then look at our students. They're born into families and communities that are segregated and isolated. They join their friends on the streets because they don't have that same coverage. If you don't know where your next meal is coming from, there's pressure in the house because you need to go out there and help because otherwise the family can't afford rent. Now the whole family is going to go down. You join your friends in the streets because that's where you go to take care of your most basic needs. And rather than find a meaningful career, they find themselves in jail. They come out of jail and they start their own family and they're further segregated and isolated because now they have a record and it just keeps going. These are two feedback loops that just keep going in the same direction.

What happens through the gym, and the reason we do this, is that when you create understanding, all of a sudden you remove the fear that separates people and these families and replace it with a functioning circle.

How do you find the kids?

We focus on young people who are actively involved in gangs. While we're focused on finding them, if we have one of our target students telling us there’s a person who's twelve who we really have to worry about, we are going to work with them too. Through our students, we're able to find the next generation right before they get there.

We are really careful about working with our specific population rather than a wider, general at risk population because honestly there are better programs than ours that can provide more structure for an at risk student versus someone who's already in this circle.

What do the early days look like when a student comes in?

Most likely we've already done a ton of work outside the gym to develop that trust to the point where they're willing to come in. That can include going to court to be by their side, not to advocate. It looks like going to wherever the hangout is to say 'hi,' and it can look like getting them a ride somewhere when they need a ride. Our goal is to slowly build that trust. While time consuming, all these little things are really quite simple. Once they're in here for the first time, our goal is to make sure that they want to come back or at the very least know that they're welcome to come back and that we like having them here. Challenging them to a game of Madden or NFL for PlayStation Four is much more effective than challenging them to a workout.

From there we get into the workout and then we have them meet our clients. We can start to build up what we call our 'individual advancement plans,' which are really about this person's dream goal. Where do they want to be in however many years? If not a career, what are they most passionate about in terms of a hobby? Can we connect them with positive opportunities within that passion? And certainly some students are going to become personal trainers, but not all. Our goal is to leverage this network and the network we have around us to connect on whatever sort of opportunities are going to be positive and meaningful.

Why do you keep your address confidential?

The reason we keep our addresses confidential is that we want them to be able to come whenever they need – whether that's once a day, once a week, once a month, once a year. Rather than trying to mix rival groups - which can create a potentially dangerous situation and would mean that we only have these very specific hours for each group - our whole goal is to create a new community and a community that our students belong to no matter what. The importance of them knowing that they can come whenever they want is huge.

You said you have many high net worth people working out here. How does that work?

In terms of how we get them?

No. In terms of what does it look like and how does it go over to have such extreme ends of the socio-economic spectrum working out together?

The more our students know about our clients and the more our clients know about our students as individuals, the more we see this form of inclusion starting to take place. It is this really organic, purposeful way to get people to know and understand each other.

Right after we opened up the Dorchester site and started signing up a few clients, one of our students who had taken on their third client looked at me and said, 'I can't believe these white people are really paying me to train them.' I sent an email to a few clients thanking them and making sure they understood how much this meant to one of our students and they replied, ‘He is changing them more than the other way around.’

I love how the chasm seems so inconsequential to you. Why is that?

For me, it comes down to understanding. It doesn't need to be this incredibly sophisticated model. It actually needs to be incredibly simple and the simpler it is, the easier it is to make things happen. The complex part is how you scale.

What keeps you up at night?

The good news is it keeps changing. The bad news is it keeps changing. We work with whom we work with. Things can go wrong at any moment. Not in the gym but in our students’ lives when they go home and they're right back in the situation. Last month, we didn't know him personally, but a close friend of one of our students was one of the guys that was killed in gang violence, and then the next day and the next week looked very different in terms of how we do our outreach and how we check in How do we best develop that support system so that they can react in a more positive way?

Also, there’s always funding as a non-profit that will keep me up. I think we're fortunate to have some earned income with our training service that allows us to leverage to build these big corporate connections. Ideally, corporations where we go train will bundle in donations at the same time, so we can help a company save on health care costs because their employees are getting healthier while spreading our mission.

We've also been very fortunate with some foundations like the Lynch Foundation and the Devonshire Foundation who have been incredible and early donors as well.

Why have you been successful reaching this population when so many others have failed?

I've been really fortunate to have this incredible support system of people like Anne Morriss and Grant Todd who are on our board to lean on for my own personal growth.

It’s funny, before we actually got off the ground as this bootstrap startup in 2010, I was speaking with different organizations who were closely working with a similar population but in a different way. Everyone had such strong opinions as to who these young people were and what they needed to do and what a program needed to look like. I look back at my experience working with some of the guys in MS13 and I remember that I was told I had no clue what the hell I was doing as a 26 year old who had joined AmeriCorps. There was this disbelief that I could actually engage them and at the same time these really strong beliefs about what this population needed. Personally, I recognized the fact that I don't know what the hell I was doing. I can't possibly understand what these young people go through on a day-to-day basis and therefore I can't possibly assume that I know what's best.

I think that was the most troubling part. There are a lot of people passing along these assumptions that they know what's best when they're not the ones getting shot. They're not the ones going in and out of jail. They're not the ones that have to deal with what our students have to endure on a daily basis. And because I've known young people who are part of this specific population and we started training at Department of Youth Services (DYS) Correctional Facility for young people serving the most severe crimes, rather than assuming I knew what's best, I assumed our students did.

It forced me to listen and rather than go in saying, 'I want our recidivism rate to be less than X percent' or 'I want X percent to go to college; I want X percent to make whatever,' all I want to do is work with the population.

Our three core values today:

– We care more about our students than any outcome

– We don't assume we know what's best. We assume our students do

– Patience

Given how many years of trauma our students have gone through, given what our students have to worry about today, we have to be patient because in the short run, some of the decisions they're making, regardless of their pedigree (I disagree with anything that breaks the law), those might be the best short term solutions that they have available. We have to respect that and at the same time it empowers us because we know it's not on us to change the world, which I think is a very false, condescending belief,

What do you think we can change?

It’s on us to try to create these new communities and not to force someone to change but to empower people with the option to change. No one wants to be dead or in jail. It comes down to this: we care about our students, we listen to our students, and we're going to be patient. That’s what allows us to work with extreme commitment to this population.

We’re dealing with scaling challenges now. We knew when we jumped to two sites that our staff was going to be spread fairly thin and it was going to divert resources. And now we’ve got this pipeline of students that we're not able to reach as well as we used to, but that's okay because I'd much rather have these logistical challenges that come with working with this population. We could have the gym packed every day but we are looking for those most at risk of gangs.

Can we talk about your journey? Was there hardship?

It wasn't tough. One of the things that our students have helped to change in me, and I think this goes probably for all our clients, is that what they're going through versus what I had to go through really gives perspective and shows what challenge really looks like. I haven't been shot. I haven't spent time in jail. I haven't been put in situations where at a young age I was trying to put food on the table and help out the family. I grew up in Amherst Mass, which is the most politically correct town in the country, in a middle-income household. My mother and father were together. It's not like we were taking trips to Dubai or anything, but we took a summer vacation. We made it to Disney World.

Where did your big heart come from?

I really enjoy doing this. I think one of the things that maybe had somewhat of an impact is that I was always an undersized athlete. One of my coaches growing up played for the Nigerian national team and as I got older, I would coach for him at the summer camps. I remember one time he asked the kids, 'who wants to be a professional soccer player?' And by far the worst soccer player there raised his hand, and I heard chuckles and I'm thinking to myself, 'there's no way that kid can play pro.' Then I see my coach, Nathaniel, very genuinely say, 'if you want to be a professional soccer player, you will be. You just have to put in the time and effort.' He believed in that kid.

What does a failure say to you?

It’s an opportunity to learn. You can have the best plan ever on paper but it’s going to look differently when you start dealing with people. Failure is just a natural process of learning.

How can we help?

Come and train at ICW.

How does one sign up?

If you go to our website www.innercityweightlifting.org and you can email Josh or myself. You can sign up online. The challenge is that we don't disclose our location. If you email us, we'll set it up in whatever time works for people. You'll get a great workout and change someone's life at the same time.

And if there are companies looking for training services and would consider hiring us, that helps too. We have a coach and student who can go to your location. It's an extremely high quality service and you impact a community at the same time.