American Composer, Artist, and Architect

Soundstair at Boston Museum of Science

Reach in NYC Subway @34th Street

Heartbeat with Baryshnikov

Sonic Forest on tour at Coachella

MLK School in Cambridge

The notion of a social foil is definitely what my public work is about. How do you make creative structure that allows people to interact with one another in a playful and creative way?

– Janney on Urban Alienation

By Heidi Legg

I love interviewing local artists who are well known around the world but whom I’ve never heard of or know little about. For me, Christopher Janney falls into that category. His Sonic Forest has been shown from Rome to Lincoln Center to the Coachella Music Festival. He has permanent work installed from Miami and Dallas-Fort Worth Airports to Cincinnati, the NYC subway, and the Boston Science Museum.

The concept that sat most with me after our interview was his concept of Urban Alienation. Janney sees his sound sculptures, which he calls Urban Musical Instruments, as a way to bring diverse groups of people into public spaces and gives them a foil through which they can interact.

And then he told me about the bees... If you put a colony of bees into a shared space with another colony of bees, they literally fight until death. However, if you put them in the same space but separate them with a newspaper where they can hear, but not see one another... their curiosity takes over and slowly they cut through the paper to weave together into one functioning group. Janney sees his Urban Musical Instruments as this foil.

For those of you who were with us in the parking garage for our Google event, you might like to know that one of the talented drummers on the stage, Ryan Edwards, brought me to Janney.

This is a cool space.

Nice to have you in the studio.

You've done a lot of interesting work.

I'm older than I look. [He’s 65 and does look younger.]

Your newest interactive music and light installation opened at the MLK School in East Cambridge this month. How did this come to be?

It was a competition, actually. We compete for the ‘1% For Art Initiative’ which is implemented in 42 states and federal law. One percent of a federal construction has to go toward works of art, and Cambridge is very avant-garde in that sense.

Thank God, for 1% For Art because that was Congress. I mean, thank God I live in the United States and the notion that 1% has to go towards works of art. You blow up the electric panel and you can't take the art budget to fix it and that's right. This has allowed me to have a career on the architectural side of my work and I really have to be thankful for that because that's not in any other country. Other countries have started to adopt it but it began here.

It was great that this project was also close by. I don't get a lot of local work. It came down to three of us and we had to present for the Cambridge community, and they're a pretty vocal community!

Was anyone invited to hear proposals for the MLK School?

I'm pretty sure it was an open meeting. At the second meeting where there were thirteen people. Usually the committee's like three to five, but in Cambridge it was triple the size.

I had brought a little demonstration machine. Some people understood right away and other people never really understood. I heard, ‘what do photocells do?' at which point one person said, 'I'm not sure about the artistic content but you know that piece at the Boston Museum… The Soundstair? Now that is really good!’ The person next to them leaned over, 'he's the same guy.'

What's the process for you in creating this work?

It’s part of a group of series I call Urban Musical Instruments. The Soundstair piece that's at the Boston Museum of Science was installed in 1989, and it was my thesis at MIT and a series I still do. It's in the Boston Children's Hospital now, as well as in other hospitals in the US. Combining architecture and music has always been my interest.

At the MLK School they have given us a hallway and it is the main spine within the school. I thought, 'okay, so, I've got a lot of people moving up and down this hallway' and as an architect, I think about stairways, hallways, rooms or circular space, and I work to make things very site-specific.

The Sonic Pass Blue at Lehman College in the Bronx was a similar condition. Very often, public art needs hardware for a space but as an architect, you say, 'okay, what's the site analysis?'

© 2015, PhenomenArts, Inc. Christopher Janney, Artistic Director Photo: PhenomenArts, Inc. MLK School installation in East Cambridge

In the case of Martin Luther King, it was, 'okay, we're going to have this hallway. There is no glass but we have lots of enthusiastic children who like to jump and reach,' and so the idea was to make a wall that's maybe seven feet tall and the higher you jump, the higher the note. That was the initial way I mapped what's going on in that space.

Are you trying to capture an emotion?

No. I think that the general idea is to create curiosity and discovery and typically, the younger the person, the easier that is to do because that's their natural state of mind.

I do a fair amount of work in school and university environments because that's a great place where you have inquiring minds and curious people. That's not always the case in a public space in the middle of New York City, even though we played with that in the subways at 34th Street for Reach in 1997. I am not only thinking about the physical conditions but about the social conditions.

Auditory is one of your big elements. How do you look auditory in 2016 given all our senses are being amped out with technology today?

I've been thinking about ways to combine architecture and music since 1977, and I'd say my ideas about composition haven't changed much, but the technology has obviously changed. We now have much better digital music systems allowing the melodic of all my work to be made from acoustical instruments that have been digitally sampled. That's allowed me to expand the pallet and think about sound in different ways. Especially when putting sound in a public space. You already have the cacophony of what’s going on in a public space. Very often I'm making things that are very melodious, very sweet, very soothing. I'm pushing against the cacophony and the high anxiety of public spaces. Conceptually, that hasn't really changed.

You remind me of a character in Doctor Seuss. Who inspires you?

I think the Doctor Seuss concept is fundamentally the right idea. I had a great friendship with John Cage, the composer, and one of his great lines that I always remember was 'how to be free without being foolish.' It’s not a question of being a child. It might be a question of being childlike, but with the wisdom of an adult.

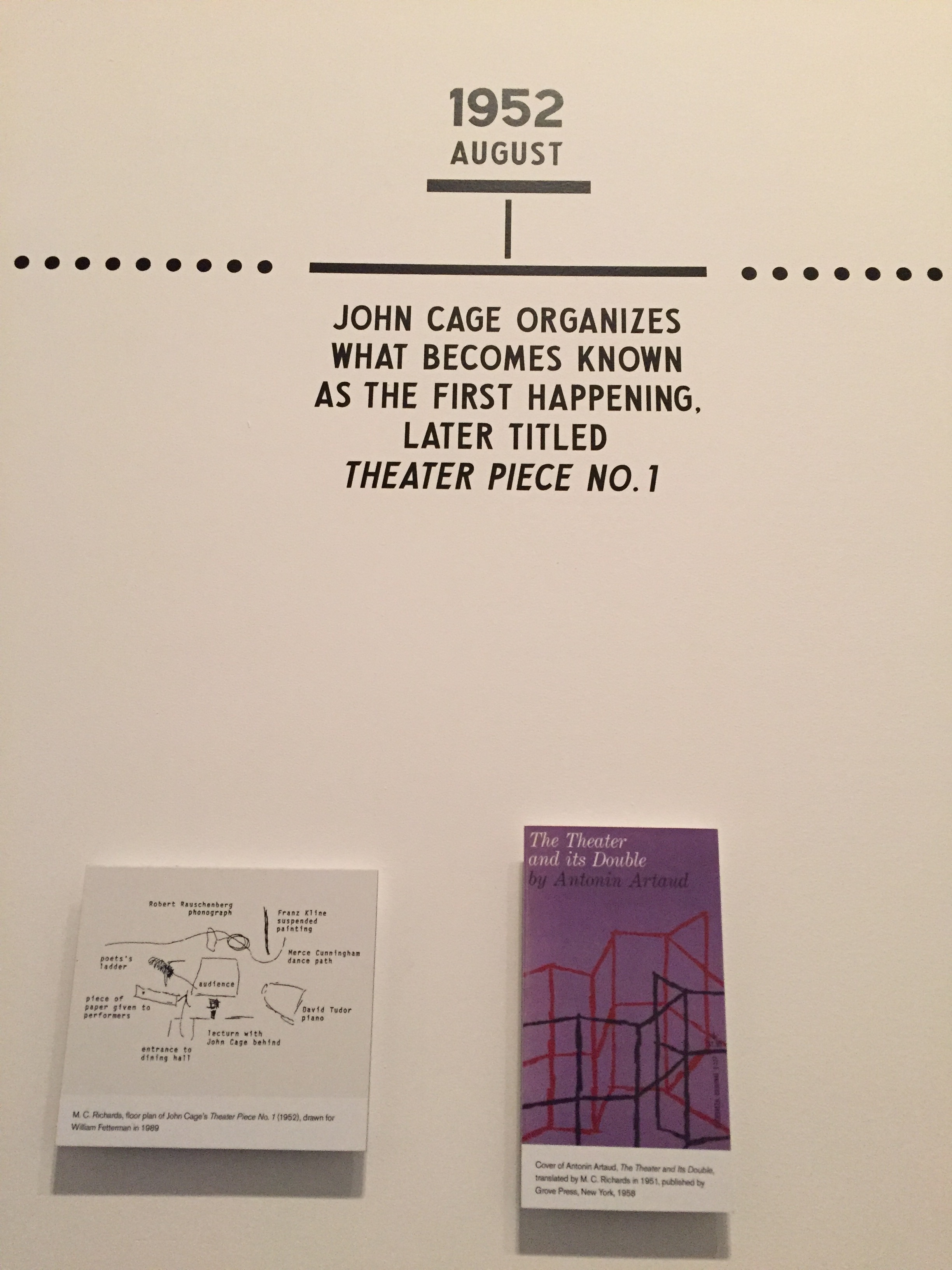

[John Cage's influence at Black Mountain College 1933-1957 is currently on display at the ICA in Boston.]

My interest is to make interesting music – interesting sound – but not to make it childish. Rather, it is to pursue those qualities of wonderment and curiosity, and people aren't really so aware of how important sound affects your perception of what you see. It’s very important that the sounds that I create really sound good. They sound rich. They sound fat. They sound full. It doesn't sound like a little video game.

Kids are dabbling on their smart phones and computers doing mashups. What does that mean for your art?

There are a lot more people experimenting with sound, which is great. I don't know how many more there are out there who are trying to combine architecture and music and bouncing back and forth between those two disciplines: trying to make music more like architecture and other times trying to make architecture more like music. I haven't run out of possible iterations.

While the Martin Luther King School piece doesn't have colored glass in it, I've done a lot of projects, especially in airports, where I've used colored glass together with the sound because you get these really great colored shadows moving across the floor and people walking next to the colored glass basically being immersed in the color. Trying to think about ways to make environments that are immersive in both the color and the sound is something I have been pretty focused on as of late.

How does your childhood influence your work?

I have a great friend actually who's an architect in New York and he and I used to build model cars together. I talked with him maybe a week ago because a very famous custom car builder – George Barris, from Southern California –recently died. I wanted to make sure he saw the obituary. He actually now has an electric car and I'm building a custom electric car so we're still very much in touch with each other again.

Is that just a tinker project for you?

I guess my mother would have said that it was all tinkering but, no, it's not a tinker project. It's a Porsche 911 with four electric motors in it. How tinkered is that?

Electric Porsche 911?

It's my day job. Everything here is my day job. I've been working on it for 4 years.

When will it be ready?

That’s what my wife says about my house, 'when's the house going to be done?' I said, 'what? It was done four years ago.' These things go on and they hatch new ideas in new directions and I’m happy to be living in the process.

You seem happy go lucky.

We all have our days.

What public opinion would you change?

There is a lot of bad stuff going on around us and so it's important to put good stuff into the world. I have a piece in the New York City Subway at 34th Street. Every week, 110,000 people go through there and experience Reach. It's both the uptown and downtown side of the tracks and it's this thirty foot long bar about six feet off the ground and you reach up and you break the photocells and you trigger sound and the sounds are like the rainforest together with melodic instruments.

Here you are underground in this manmade space; you're holding your purse or your briefcase pretty tight. There's a lot of anxiety there. It’s a perfect place for the kind of work that I do because I can cut against that energy and put this sense of curiosity and sense of playfulness into this otherwise high anxiety place and that's what I like to do.

The idea behind the Urban Musical Instrument is to go into places where there isn't a lot of joy or curiosity – understandably – and put something like that in there because on many levels it's a natural state of the human condition to be curious and to wonder and to have imagination. As an architect, doing works in those kinds of places is really intriguing.

Are there some locations where you would love to kit out?

I'd love to put the Sonic Forest, which is a touring big music festival with a series of sixteen columns and a hundred sensors, on a world tour. It’s like a communal musical instrument and the sixteen columns are each about ten feet apart. So, you more or less have about a thousand square foot immersive sound and light environment, and I've often wished that I could make one with a hundred columns and take it on a world tour and put it in front of the Notre Dame in Paris and put it in Trafalgar Square in London, and then put it in front of a mosque in Istanbul.

I would love to take this Urban Musical Instrument and put it in these different urban cultures around the world and really watch how it interacts as almost a cultural barometer.

Those are some of the ideas and the kind of dreams that I think about. Where would be great places to put this work that would in a sense affect social change? It would be very much in John Cage's spirit. It's not so much to try to make something change as it is to set up an experiment and observe how it works in this environment. How would it alter this environment and how would it alter me in this environment?

What do you think are your most successful projects?

It would actually be the piece Heartbeat that I did with Mikhail Baryshnikov. I put a wireless heartbeat monitor on him so that you heard the sound of his heartbeat as he was dancing. I trained as a drummer and while I was at MIT, I remember thinking everybody has a drum inside them. How can we make this a part of a performance? Then I went about and I asked different colleagues around the institute, 'I'm looking for a way to do this... any ideas?' and somebody would say try this or that. By trial and error, you sort of get to where your concept started. But then when I first put it on the dancer Sarah Rudner from Twyla Tharp, it was so much bigger than anything I had ever realized.

To hear the human heart amplified on such a great performer as Sarah Rudner or Mikhail Baryshnikov… I could never have imagined the power. I said, 'who thought this up?' It wasn't me. I think if you read a lot of biographies about artists, they talk a lot about being a conduit through which ideas come and through which ideas happen and when I feel that, that's when I feel like, 'okay, now I'm in the right place.' It's not me but it's coming through me, and I'm the person that's helping to bring it into reality. It's very much so with Heartbeat. That was and continues to be a really great piece. I've done it with the A cappella group The Persuasions and Emily Coates from New York City Ballet.

It's so obvious but it wasn’t.

Of course. It does seem obvious but when you hear it, it's the subliminal power of the heartbeat and we have a thousand-seat-theatre and there's Baryshnikov solo on stage. Wow. We travel with a special sound system so it’s basically tuned to the space and you feel like you're inside his body. He's just this little guy but his heartbeat is filling the whole room. It’s really indescribable and this is an experience I could never have had any other way.

Did you do a lot of drugs when younger?

No. It's a good question and I didn't. I did some drugs. I did enough to make me realize there's something inside of me that I'm never going to get out of a classroom and now I have to think about how to do this in real life. I got very into meditation and very into Eastern philosophy because they are talking about the same goal, but you have to learn how to integrate it into your daily life. I became pretty serious about doing those things.

What important thing are you working on right now?

The next project after the MLK School is a piece for the Oklahoma City Airport, and it's a colored-glass-immersive-sound piece. It's actually a vestibule going into a building and the sound is environmental sounds that are indigenous to Oklahoma along with melodic instruments.

I've gotten into 3D printing and I've investigated certain companies now that can print in clear acrylic. This is the 1/8th inch thick but the idea is if now I can also make it in clear on a 3D printer, then the next step is to make it in transparent color. They’re not quite there yet and often that's what happens, especially with Heartbeat, where I think of the idea long before the technology is developed. I had to wait for the technology to catch up.

Why do you want it transparent?

I’m working on some new models and I want the colored shadow condition. In the end it's a model that's maybe a foot and a half tall, but it's a model for something that wants to be ten or fifteen feet tall that that you’ll be able to walk into.

That's really a concept that occupies my imagination when I'm not having to solve a specific problem for a specific project: Large-scale, transparent color environment that will also have sound.

It's like you're designing Doctor Seuss' pages in real life.

I consider that a great compliment. His books are still a great inspiration. I read them to my kids. I read them of course growing up. My son is a songwriter and musician in Los Angeles and lyrics are very important to him and when I look at a Doctor Seuss book, I say, 'Goddamn, these are lyrics.' The way he gets the words to rhythm and the cadence are very much like John Lennon.

How can your work help our over-stimulated society?

I think the thing that fascinates me about the cell phone, socially, is that here you have this instrument with Instagram and Facebook that allows you to communicate with your friends, yet people are walking down the street and all they're doing is looking at their cell phone. You have this instrument to communicate with people only it doesn't help erase what I call 'urban alienation.'

There is a theory that the cities are so dense that people can't build communities because there are too many people. The hope on one level was that the cell phone, with social media, would break down these walls and allow for social interaction, but it doesn't. It only allows for social interaction with your friends who aren't next to you.

The Urban Musical Instruments that I make are ways where people physically interact with one another – total strangers in public spaces.

If you give them a structure within which to interact that is creative and playful, then they enter into that. There's a theory that if you take one colony of bees and another colony of bees and you put them right next to each other, they'll fight each other to the death but if you put a piece of newspaper between the two colonies and they can hear each other, they'll systematically eat away the newspaper and, in doing so, they won't kill each other because the social foil of the newspaper has allowed them to interact with one another in a positive way.

The notion of a social foil is definitely what my public work is about. How do you make creative structure that allows people to interact with one another in a playful and creative way?

Favorite place to hang out in Boston?

There's a great restaurant Moonshine 152 in Dorchester. Asia is the chef. The cool thing is that it's open until like two o' clock in the morning. If you go in there at midnight, half the crowd is people in the restaurant business who have closed their restaurant or bar and go hang out there. I'm a night owl. I love to find places where there are things happening late at night.

Another night owl spot where you go for music?

The Beehive. I like small, intimate places. I don't really like going to House of Blues or places like that.

Favorite upcoming musician?

Dance group out of New York called the Dance Cartel. They’re pretty happening. They do the whole thing on the floor in a club. One of the dancers danced Heartbeat before. She's a good friend and a good dancer but their whole sort of take is on immersive and participatory and I’d say they're getting some good traction, which is great.