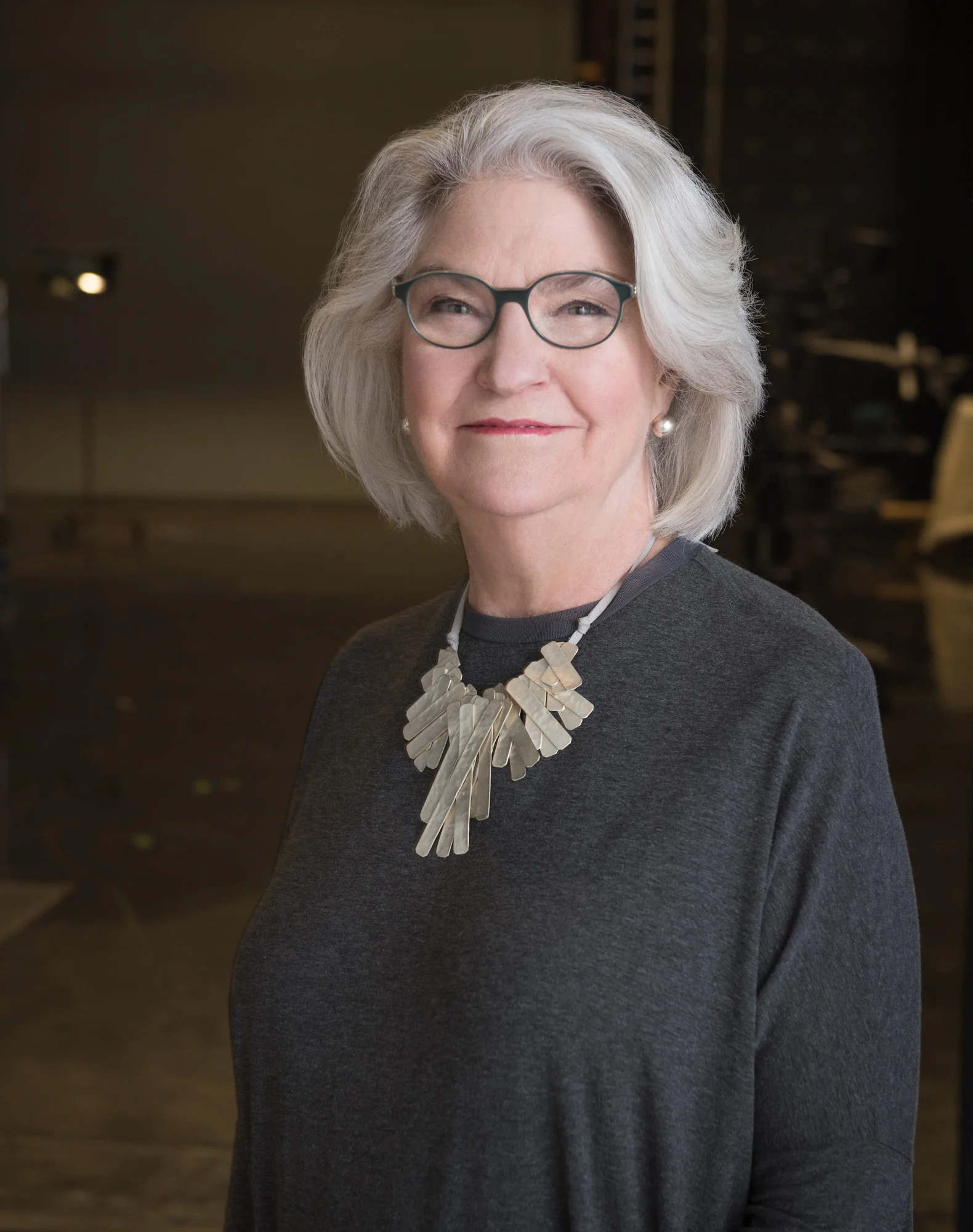

Executive Producer

PBS Masterpiece

Downton Abbey, Sherlock, Wolf Hall

OBE

Julian Fellowes created the world of Downton Abbey and twenty major characters and their storylines. He was ready to tell this story. He knew the world. He loved the world and that's when you can have magic: when you have a creative person who finds their subject.

Interview by Heidi Legg

Rebecca Eaton, The Emmy Award-winning producer of PBS’s Masterpiece, has brought us many beloved television series over her thirty years at Masterpiece, based here at WGBH in Brighton including the sweeping Downton Abbey series that will air its final episode this Sunday, much to the despair of its lulled audience.

Eaton, who had long been the helm of the PBS series Masterpiece Theater and Mystery!, oversaw a highly successfully relaunch of Masterpiece in 2008 which attracted a new generation of viewers. She has brought American audiences Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall, the recent hits Sherlock, Poldark and Downton Abbey — the most-watched drama in PBS history — as well as such high-profile titles as Mr Selfridge, Endeavour, Wallander, Prime Suspect, Cranford, Little Dorrit, Inspector Lewis, and The Complete Jane Austen. Under her leadership, Masterpiece has won 55 Primetime Emmy Awards®, 15 Peabody Awards, six Golden Globes®, and two Academy Award® nominations. In 2011, Eaton was named one of Time's 100 most influential people. Her distinguished career has earned her the official recognition of Queen Elizabeth II—with an honorary OBE (Officer, Order of the British Empire). Viking published her memoir, MAKING MASTERPIECE: 25 Years Behind the Scenes at Masterpiece Theatre and Mystery! on PBS in 2013.

What intrigues us about Eaton’s fascinating career is not only her skill and success at building up a brand she calls “The Little Black Dress” of television, but her experience and appreciation for story, as well as her insight into what she explains as “the magic when an artist finds their subject.”

Q&A

How does your love of stories inform your Masterpiece mission?

My first experience of storytelling was having my father tell me bedtime stories. He would make them up and lie on the floor of our bedroom, telling us stories about Willie the Whale with the Detachable Tail and his girlfriend Susie. And then reading came easily to me and I would go places reading: I would time travel and fly around the world and to other countries, particularly England. I had a real love from the earliest time of all things English.

For a bookworm, and as the daughter of an actress and an English professor, I think it's the perfect job for me. I love good writing and drama, but there was always a little showbiz in the air because my mother had been on Broadway and she'd made some movies.

I had never ever intended to do this job. I was a documentary filmmaker because I loved to hear stories, I loved to get to know somebody – much as you're doing – and profile them to really figure out who they were, and then give my version of it. I had never thought about making drama or being close to anybody making drama. In fact, when this job came up, I thought I shouldn't even apply. It turned out to be perfect.

You started thirty years ago with Masterpiece. What did the job look like then?

Well, it was a lot of what it is now. The executive producer of Masterpiece is the person who chooses which British programs will be included in Masterpiece, and it means looking at a lot of shows that are already made, reading scripts, and choosing the ones that would suit this audience. It's a dream job! I talk to British producers about their hopes and dreams for upcoming shows and to those who are taking pitches, and then we fund those productions to make them possible. We don't make them here. They're made by British companies and British broadcasters – for the BBC and ITV – and once they're done, we bring them back here. It’s also my job is to make sure the whole country knows about Masterpiece and knows about whatever show is being produced. There's a great deal of publicity and marketing to be done. I also have to raise money.

You're a curator of sorts.

Yes. Curator is exactly the word.

How many productions do you fund a year?

It varies. It’s more the number of hours. It can be a few very long running series like Downton Abbey or Mister Selfridge or Indian Summers. And there were years when we would do ten or twelve very short mini-series like Mrs. Brown.

Mrs. Brown was just one night, but it was a very important title. Masterpiece used to be much more of a mix of mini-series, singles, and long-running titles. Now we're back in the age of long-running titles as we were with Upstairs Downstairs, The Duchess of Duke Street, and I, Claudius.

Why do you think that is?

Because of the technology of choosing when you want to watch a show. You can do that now. You don't have to sit down on Sunday night at nine o' clock. Many people like to watch TV the way they read books. They like to dig in, read a whole bunch of chapters or screen a whole bunch of episodes at once. A series of ten or thirteen hours is very satisfying for the audience and it's also cheaper to make. You can amortize the costs over lots and lots of hours. From a production point of view, if you have to find a location or get everybody to a set for one hour, it's a very expensive hour. But if it's over many episodes, it's much cheaper.

What do you think contributes to this Golden Age of public television we're in?

I actually think it's a Golden Age of television, not just public television. As a viewer there were years when I couldn't find anything to watch anywhere else but public television. Now, I can find really interesting things on HBO, on Netflix, on Amazon. Still, public television is usually where I end up as a viewer because I like a smorgasbord of programming. I want documentaries and dramas and history programming – you can get all that on public television and I know the quality is going to be good. I think the quality of material that's happening on public television is as good as it’s ever been. Nobody else does journalism, except Frontline. Nobody else does serious science, except Nova. Nobody else does serious American history like The American Experience. I do feel we have absolutely achieved the goals that we all set when public television started. I joined public television in 1971, when it was a year or two old.

Public television led the way. Masterpiece is forty-five years old. We've always had quality drama, and Nova is not much younger than Masterpiece. We've always been there and now, largely because of cable and Netflix and Amazon, more people are doing better, smarter television and a lot of movie writers, directors, and actors are migrating to television.

How does that change the game for you?

I think it focuses the mind. It means we have more competitors for high-end British drama than we have ever had before. Over my thirty years of doing this, there have been competitors but they came and went. A & E had an idea to do period drama, as did BBC America. We would compete with them for titles, but then they changed their brief. We don't change. We are the little black dress. We're always in fashion, always elegant, and always high quality.

The current landscape does make me aware of our audience and who they are – and they are an incredibly loyal group of people. They are people who tune in at nine o' clock on Sunday night no matter what's on, because they know it will be good. They're also the people who tend to support their local public television stations and are therefore the lifeblood of public broadcasting. I am very mindful that job number one is to satisfy them and to keep them.

It says to me that we have a niche. It's very hard these days to define oneself differently from everyone else and I think we can say who we are with great confidence. And I don't think there'll ever be a brand like Masterpiece again. It's such a crowded field and we were first - we were here and we stayed here, which is also unique to public television. Commercial television would've abandoned us in the thin years and there were thin years… Public television didn't. At one point, we lost an underwriter we had had for years in Exxon Mobil, and public television stepped up and paid for us until we found other underwriters. That wouldn't have happened in commercial television.

The incredibly popular Downton Abbey is ending. How do you know when a series is done?

It starts and finishes with Julian Fellowes. When Julian Fellowes says it's the end, it's the end because he writes every word. He created it, he writes it, and he dreams it. He acts it out in his head and when he decides it's time to head for the barn, we all go to the barn.

I always had a feeling that it would last about this long because traditionally television runs about six seasons – sometimes longer – but that's about as long as most actors want to stay with something. By then, the people who created it are ready to move on to something else. They are very aware that they can stay too long at the fair and begin to repeat themselves or dry up. He picked the right moment – it's exactly the right moment because people are so upset that it's ending.

Julian Fellowes first broke out when he wrote Gosford Park for Robert Altman. How did you see him change over the course of the series?

Well, he hadn’t been a director. He was an actor. As he would say, ‘a mediocre actor.’ He was the perfect character actor because he's kind of a portly guy and he was on British television. I sort of knew who he was, as he’d done a few movies and, wrote the book for the musical of Mary Poppins, and wrote Gosford Park. I was aware of him but I have to say I didn't sit by the phone waiting for a Julian Fellowes project to show up. Then the head of Carnival Film & Television, an independent company in England, took Julian out for dinner and said to him, 'would you consider making Gosford Park into a television show?' Apparently Julian went home and two weeks later came back with twenty pages of the story.

He created the world of Downton Abbey and fifteen or twenty major characters and their storylines. He was ready to tell this story. He knew the world. He loved the world. He probably wishes he had lived in the world and that's when you can have magic: when you have a creative person who finds their subject.

What scripts have surprised you over the years?

I remember a very specific moment when I had a physical reaction to a show. In fact, I remember two of them: my heart started to beat faster, I started to smile, and I had a sort of tingly feeling because I knew they would work.

The first was a small mini-series we did ages ago called A Very British Coup, which was based on a novel by Chris Mullin. It was back when Masterpiece used to do a lot of acquisitions and it was a political thriller of a socialist prime minister elected in England. He's a hero and he's going to change the country, and then someone comes forward who has a secret about him from his past. At the time when I screened it, we were not doing these types of programs at Masterpiece. We were doing frock dramas. We weren't doing anything contemporary, or anything even mildly set in the future. I was on the edge of my seat to find out what would happen. Except for the fact that is was contemporary, it had everything else that Masterpiece is about, and I really wanted to try it out on the audience.

They loved it and it won an Emmy. It opened the door for contemporary drama on Masterpiece of which we don't do much – but when we do, it works. I knew it when I saw it.

The other time was also a show that was already shot by the BBC, and it was the story of a political operative in England in the House of Commons whose name was Francis Urquhart. He was a nefarious presence who basically manipulated the government and it was called House of Cards written by Andrew Davies, who is one of our house geniuses. He's written so many great Masterpieces. He's in the UK – they're all in the UK. It was a book adaptation and it was so witty and so clever and so possibly real. Of course now it's on Netflix with Kevin Spacey and it’s been redone, but it had the most wonderful theme. It had this processional trumpet solo and I remember, I was screening it at work, and when the credits came on at the end with that theme, I just jumped off the couch and did a little jig because I had found something great. Andrew won an Emmy for it and then it went to three or four different seasons.

The other was the script of Mrs. Brown starring Judi Dench as Queen Victoria. That was sent to me and I said 'yes. Absolutely.'

Are there any that got away?

There have been a couple of scripts that I've read and thought, 'we have to have this.' One of them we didn't get and it felt awful not to get – I was furious – was the script of what became the movie Truly Madly Deeply with Juliet Stevenson and the lovely late Alan Rickman. It’s about a woman whose husband dies - it's about grief - and I thought it was one of the most beautiful things I'd ever read. It was really about something and I tried desperately to get it, but they made it into a movie so we couldn't have it.

You have the coolest life.

I know. I know.

What are you working on right now?

I am screening cuts of the new Poldark series and one about Queen Victoria, called Victoria, which we're co-producing. There’s also a second season of Home Fires, which is the lovely series we started last year about the women in a village in Cheshire during World War II who were left when the men went off to war.

What do you look for when you screen cuts?

I give notes back to the production saying 'this scene didn't seem to play right or there was something off here or why is this character…' You know, notes back to the editing room.

Are you very active in producing the series?

Yes. We're not the final word because we're not the most money. The broadcaster, the BBC or ITV, usually has the final word because they put the most money in. They are either made in-house at the BBC or ITV, or they're made by independent companies and we license them stateside. And that's another part of my job: to negotiate the deals and make sure we get all the rights that we need.

How can viewers in the US be involved?

The main thing they can do is support the Masterpiece Trust, which is something that I created maybe six or seven years ago. It is for high-end donors and it happened at a time slightly before Downton Abbey because I realized that Masterpiece was subject to the vicissitudes of any public television show. We might have a funder. We might not have a funder. Public television might have money. It might not have money. The people who care the most are this very loyal audience, and that’s why we created the Masterpiece Trust. It goes directly into buying new British programs.

It was hard to get it started because every station in the country, including WGBH, raises money from donors in this community to keep the lights on. Now, here comes yet another voice saying 'give money to us,' but we figured it out. For instance, our most generous donor is Darlene Shiley, from San Diego, and part of her gift goes to her station in San Diego then shares the gift. There is more information about the Masterpiece Trust on the website and that is the way people can support us, in addition to supporting WGBH locally.

When you look at all the creative talent you work with in this industry, how do you encourage them?

I have a daughter who's a writer, so this is a very timely question. I also think about it for myself as I think about what I might do next. My advice is to first of all read and listen. Make sure you're paying attention to what's going on either with somebody that you're talking to or in the world. Reading allows you to understand, deeply in your bones, what good writing looks like, what good dialogue looks like, and what good storytelling looks like. Really immerse yourself in that because once you have it, you'll know it when you see it and you'll be able to recreate it yourself.

As they say, follow your passion and listen to yourself. What are you really, really interested in? If it's a place where you want to live, a story you want to tell, somebody you want to be with, a lifestyle you’d like to live – really listen to that. Don't force yourself to do something that doesn't fit you. Keep your eye on what you really, really want. You may have to do other things to pay the rent, but really follow your own lead.

Would you say this applies to Julian Fellowes with Downton Abbey?

Yes. And be patient because sometimes it takes a long time and sometimes you get lucky. I feel as if I did.

What public opinion would you like to change?

I wish people would wake up and realize how necessary it is to have a broadcaster who's completely removed from commercial and editorial influences, and see that it is funded in a way that would allow us to do our work. It's chronically underfunded. I wish we had a more robust public broadcasting system.

Another thing, I'm not sure if 'public opinion' is the right word, but what worries me is narcissism in our culture. There is a self-involvement and there is distractibility with people, whether it is from a handheld device or an inability to sit and really listen to somebody else and not think about oneself. I worry about a creeping insular selfishness about us as a culture in this country. Whether it's in our foreign policy – hunkering down and being terrified and protective – or trying to shore up as many things in our houses as possible to make us feel better. That worries me.

Does this line of thinking affect your program choices?

Yes, I do think that's one thing about Downton Abbey. Even though it's history and it's antiquated and it's an idealized world, there are very good values in there. There's a value of community – of people looking out for each other – and of supportive alliances in unlikely places. Whether it's Mary and Anna with connections between those from upstairs and downstairs, or between two downstairs people who you think, 'how in the world?' They come together and support each other. I love that. That is, I think, Downton Abbey’s secret weapon.

Favorite Downton Abbey character?

Robert, Lord Grantham. I feel like he's actually an executive producer: Things are always going out of his control and the people aren't doing what he tells them to do and he's completely baffled. I relate to him.

Where do you go to unwind in Boston?

I go home. I live in Cambridge and I have the most beautiful back porch.

Where do you go to have a cocktail?

My back porch – looking out over the trees and into the neighbor’s backyard. My favorite cocktail is a Manhattan or a Martini.

Where do you go to unwind in London?

I walk out the door wherever I’m staying and hope to get lost. I love to walk in London to discover new places: preferably bookstores, parks, and shoe shops.

Character you would most like to play for a day?

Ross Poldark: to ride across the bluffs of Cornwall on my steed.

What are you reading?

Right now I'm reading Gloria Steinem's new autobiography, My Life on The Road. I have a book of books: Everything I read, I write down. [We asked her for a list]

Some of my favorites are:

Hold Still by Sally Mann (Memoir)

We are Called To Rise by Laura McBride (Novel)

On The Move by Oliver Sacks (Memoir)

Plainsong by Kurt Hanuf (Novel)

The Hare with the Amber Eyes by Edmund de Waal (History/Memoir)

The Road To Middlemarch by Rebecca Mead (Biography/Memoir)

Nothing Daunted by Dorothy Wickenden (Biography)

Don’t Let’s Go To The Dogs Tonight and sequels by Alexandra Fuller (Memoir)