Portrait by Alan Savenor

Harvard Clinical Professor Of Law

Director, Criminal Justice Institute

Senior Fellow, Jamestown Project

Emerson once said our democracy was in danger of sleeping. Not so much anymore. I think people are awake and they're going to stay awake and stay engaged - that's a good thing.

By Heidi Legg

I am humbled to bring you our 100th visionary interview on TheEditorial.com. And the timing to capture this voice who can talk to us about the power of the judicial branch in our government is apt. Four years ago when I sat down with Pedro Alonzo and Pattie Maes as my first interviews, I knew only that I was surrounded by some of this country's greatest minds along the Harvard, MIT and Kendall Square corridor. Of course, there are great minds across our nation but they are clustered here – and even those who don't walk those hallowed halls are living and working here to participate in the great experiment of what is possible. It's certainly not for the weather, easy parking or affordability! I am grateful to all the people who were willing to be interviewed, verbatim and at length, on topics of national and global interest around emerging ideas along this unique brain trust along the Charles River. In this digital age, it seems only right to record and try to decode what I am seeing around me and hope you will share it.

Ron Sullivan Jr. is important as our 100th because of his deep understanding of the US judicial system at this moment in time when the third branch of our government has moved from its quiet confidence and roared its voice. Add to this, Sullivan Jr.’s work around US incarceration reform and civil rights. I had to be patient to have a chance to sit down with Sullivan and I am grateful to to bring you this interview. His ideas around bias and the destruction of our black and brown men's lives fold into his thinking for how we move forward from the past, how we work to think collectively as “We” in our nation. He says that what has played out in the past few weeks demonstrates that our democracy was built to survive one person. He also cautions that this requires everyone to participate, to be open to conversation regardless of our baggage. We all have it, he says, and I agree. I had ruminated a long while on who would be our 100th and I could not think of a more timely and thoughtful voice.

This is quite the moment for the American judicial system. This, the third branch of government, seems front and center. What do you think about it?

It is an incredible moment in history and incredible for a couple reasons: One, we've seen for the first time in a long time how average concrete people are fully engaged in the legal system. You hear people effortlessly talking about en banc appeals and all of these arcane legal terms. I think it's a good civics lesson that people see how the separation of powers works, and how executive power can be constrained by the judiciary in appropriate circumstances. The second:

I think what we're seeing is evidence that our democracy can survive one person. It's built to be clunky. It's built to slow things down, and that's important. This executive order was a rush to move very quickly, but as we see there are three branches in our government and one of the other branches essentially said, ‘we have to slow down, figure this out, and make sure that it’s consistent with our constitution and our founding ideals.’

I do think with the recent election some people thought that the democracy was going to instantaneously implode or explode, but the democracy is robust. It doesn't work by itself. We have to work with it and so long as citizens are engaged, the democracy can survive.

Did you see the public more anxious than those of you in the judiciary and legal system because you understand this?

I think you always feel anxious, and I certainly did. It was a relief when the system worked as it was designed to work.

You're a justice system reformer. Have you seen improvements in the system?

I have seen some improvements but regrettably some things are as bad as they were twenty some odd years ago when I graduated from Harvard Law School.

What are those things?

The treatment of black, brown, and poor people in the criminal justice system – it's abysmally poor. It was then. It is now. The incidence of wrongful convictions has remained constant. Those haven't abated in a meaningful way and, last, the distribution of resources across the criminal justice system has remained unduly weighted toward the government in such a way that the accused simply doesn't have a fair shot to prove his or her case in court.

We too often see color as a proxy for criminality, it results in black and brown people being over-policed and over-prosecuted and over-sentenced.

When you look at black/brown convictions, what improvements would you like to see implemented?

That is a huge question. The central problem that we have to get at is that we still live in a country where far too many see color as a proxy for criminality. In as much as law enforcement, prosecutors, and judges, those people at the helm of the apparatus of our criminal justice system, are members of this culture, they too are impacted by or infected by some of the biases seen in the broader culture. Because we too often see color as a proxy for criminality, it results in black and brown people being over-policed and over-prosecuted and over-sentenced.

One way we have to get at this is outside of the legal system. We have to deal with a culture where different people are thought of as a ‘They’ instead of a ‘We.’ The famous philosopher Richard Rorty wrote that we have to engage in more ‘we’ talk, and I think that has to be a fundamental.

Now, if you go inside the legal system, I think the problem of disparate treatment can be addressed if prosecutors' offices begin to actually do econometric studies which demonstrate the disparate treatment by police, the disparate sentencing, the disparate sharing recommendations in prosecutors' offices, and began to address that internally.

Would you explain that more simply for us?

I'll explain it by way of an example: an economist and I are working on an experimental study here at Harvard that will happen in a prosecutor's office. You look at the same police report but on one of them you have a characteristically or stereotypically African or African American name and then the same one with a stereotypically Anglo American name and see how that plays: what does the prosecutor recommend as a sentence? Is the case actually what's called ‘papered?’ Is it actually converted into a formal criminal charge?

If your findings prove this is happening, do you think this information will help educate prosecutors and officers about this bias?

It will begin to educate. I'm not one who thinks people wake up in the morning and say, ‘you know what I feel like doing today? Let me go and wrongfully incarcerate some black people.’ The notion of implicit bias is that we don't know that they operate on our decisions. I've got many suitcases right behind me.

We all have baggage. The key is to acknowledge these biases and know that they're operating. Then you can intentionally and consciously do things to get around them. And that takes work.

I have an African-American friend who is really good at pointing these out when we are together. I really value her insight and what we’ve learned together.

People of good will can and should be able to have those conversations because, again, people who are operating with pure malice, that's a different question and you can deal with that, but I'm still an optimist. I think most people are people of good will.

When you say resources, do you think they are misapplied? In our interview with Kaia Stern, she spoke about education resources in the prison system.

You need more resources across the spectrum in the criminal justice system. Where I would focus first is with public defenders. Public defenders are the most under-resourced entity in the criminal justice system and they are the front lines in terms of representing people who otherwise can't afford competent representation. We have these systems currently with extraordinarily perverse incentives.

In most states around the country – and this is going to horrify you –there is a ceiling for which a lawyer can be paid for a felony case and let's call it $5,000, and that’s probably high in some jurisdictions. For a serious felony case, which could take weeks and weeks to try, what's the incentive there? The only way an individual could make a decent living is by volume. Leaving an incentive to get rid of that case as quickly as possible to get the next one and the next one and then the next one, rather than some sort of fair payment system that incentivizes ‘good’ lawyer-ing as opposed to ‘fast’ lawyer-ing.

It sounds like the health care system! In our recent interview with Dr. Annie Brewster, she said the 15-minute increment billing is making America sick. There just isn’t the time to spend to get it right.

Yes, a very, very similar analogy. Other jurisdictions have an institutional defender system where the public defender's office is paid by the state and public defenders are usually paid less than the prosecutors. They have these massive caseloads that result in them not being able to spend a lot of time on the individual case, and then they miss things.

I ran a recent exoneration project when the District Attorney of Brooklyn asked me to design a conviction unit and to come and get it up and running. I had one case where a guy was arrested after he returned from Disney World with his family, and they said he had committed a murder in Brooklyn. He told everyone who would listen that, ‘no, I was in Disney World,’ but he was arrested, he was charged, and was ultimately convicted. He spent over twenty years in prison until my team looked through the file and found a receipt in the prosecutor's file and in the police file that showed and proved that he was in fact in Florida when he was allegedly said to be in Brooklyn, committing the murder. Again, this is a case where his public defender simply didn't have time or resources to pour through all of the documents.

That's heartbreaking.

It's heartbreaking. He spent some twenty odd years in prison for a receipt.

The bail system is another aspect of the criminal justice system that really impacts poor people. Here is what happens: people are faced with this choice that offers no right answer. A person is arrested and, let's say, a judge sets a $500 bail. You and I could call a friend or family member to bail us out in ten minutes. For many, many people around the country, $500 may as well be $5,000 or $50,000 – they don't have it. Their family doesn't have it.

Here’s an example of the sort of conversation that public defenders are unfortunately forced to have with people around the country:

Defender: ‘Mister or Miss Client, you've got $500 bail. I've been assigned to you as your lawyer. What do you want to do?’

The client: ‘Look, I'm innocent. I didn't do this.’

Defender: ‘All right. Well, we'll go in there and we can say that and they will set the trial date. Looking at the judge's calendar, it'll probably be three months before there's a trial date.’

The client says: ‘what do I do in these three months? I've got a job. I've got a kid. I can't miss three months’ work. I can't sit in jail for three months.’

Defender: ‘Well, the prosecutor is offering a plea to a lesser charge. So, if you plead guilty to this, you'll get out today but if you tell me you're innocent, then we'll wait for trial and unfortunately you'll have to wait in jail.’

Are there foundations out there right now or wealthy individuals who have set up a way to provide this kind of bail for those in need?

Not really. There is actually a better alternative. Money bail is a horrible proxy for attendance at court. The better use of resources, and there are people and entities that are using their resources to reform the bail system, is to have a class of cases for which people are preventatively detained. That means: Murder, rape, mayhem sort of thing. There's a statute that says that those people can be detained until trial. While all other people are presumed to be released, but with conditions sufficient to ensure their presence; whether it's meeting a probation officer once a week, calling a probation officer once a day, wearing an ankle bracelet. There's a range of things short of incarceration.

There must be technology today that can handle this surveillance until the court date?

They have the GPS ankle bracelets that can monitor where you go until your court date. That would work.

Are most of these convictions drug related?

You hit on another big issue. We have criminalized drugs in a way that it really doesn't treat the underlying medicinal issues that really are animating the behavior. Now, we're seeing a lot of movement with heroin. Many jurisdictions are beginning to treat heroin as a medical issue and an addiction issue, as opposed to a criminal issue. And we're seeing the move to decriminalize small amounts of marijuana.

The USA has one of the highest incarceration rates in the world. We incarcerate 6 to 10 times more people than our peers in the developed world. What are we to do about our prison problem on a national congressional level? I’ve heard you mention change the bail system, fund public defenders, decriminalize drugs. Are there others areas we need to consider?

Yes, globally we have to realize that the criminal law is far too blunt a tool to deal with some of the social problems that we have. This notion that we simply lock everybody up and that's going to solve the problem has led to massive incarceration, a massive criminal industrial complex, and profit making prisons – which is just grotesquely offensive.

We have to begin to treat problems in their proper context. We live in a political economy where politicians are rewarded for being ‘tough on crime.’ This has led to legislators writing a host of draconian laws that criminalize everything and incarcerate darn near everybody, and they are rewarded for it. At some point the public has to say: ‘I know that it's going to be injurious to us as a culture if so many of our young men are behind bars between eighteen and thirty four.’

Aren’t we already there?

We certainly were there in the African American community. The numbers are just extraordinarily sad. We have one in three African American men between the age of eighteen and thirty four with some connection to the criminal justice system, either in jail or probation or parole, and that is just not sustainable.

You were a classmate of President Obama and served on his transition team. We had eight years of him leading us and I know some improvement has been made, but if progress wasn't made under him, is there any hope now under President Trump?

What we have to understand is that the business of the criminal law is in the states. The federal government only has about 2% of the criminal law enforcement while 98% is in the states. While I think President Obama could have done more as president, there's a limit to what any president can do with only 2% of the funding. President Obama seized contracting with the private prisons, which was a good thing, but again that represents an infinitesimal fraction of the prisons in the country.

I did notice in my research a chart that showed that most prisons in the US are in the southern states? Why? Is this based on being state run? Is there a propensity in some states to lead incarceration?

That's a very complicated question.

I don't know if you've seen the amazing documentary on Netflix called The 13th about the 13th Amendment, which outlawed slavery. There is a little clause that many people had not really paid attention to. It said, ‘except in the case when you've been convicted of a crime.’ So, it outlaws slavery and indentured servitude, except if you've been convicted of a crime upon due process of law. So, many scholars believe – and I share in the belief – that the location of so many southern prisons was a way to control black bodies in the South using the criminal justice system as a new form of segregation or even a new form of slavery. You still see the chain gangs are very popular there, where not only are people in prison but they are providing state and county services for essentially no pay whatsoever while they're in prison.

So while they are in prison they have to do state work, unpaid? What kind of work?

It’s cleaning up, highway work, building things, making license plates. They are paid like two cents a day – something like that. The notion is that this has become yet another way to control black bodies and control these populations, and I think there's something to that.

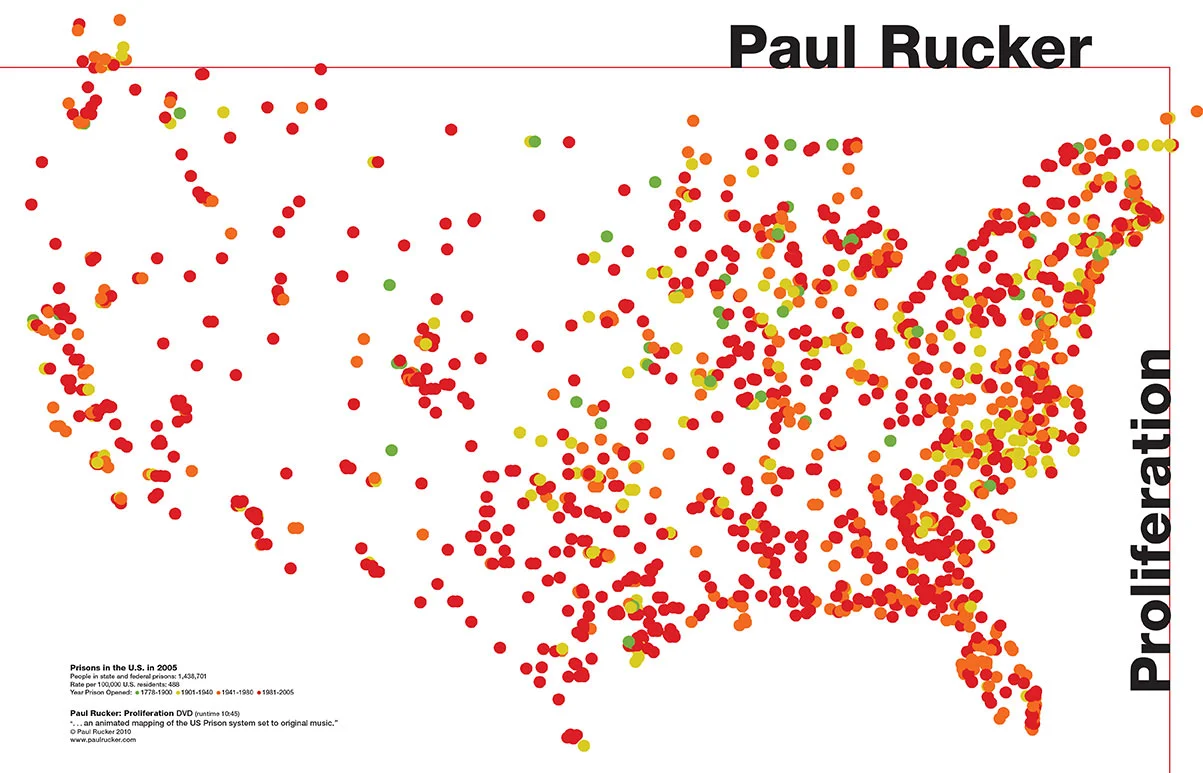

Artist Paul Rucker created an animated mapping of the US Prison System in 2010 during a two-week residency at the Blue Mountain Center based on the proliferation of federal and state prisons in 2005 based on GIS maps by Rose Heyer which modeled the growth of the US prison system.

You represented the family of Michael Brown and since we’ve seen escalation around the Black Lives Matter movement. What needs to be done to keep the priorities of Black Lives Matter in focus?

I think that it kind of goes back to what we were saying earlier – we need more ‘We’ talk. We need more of a recognition that these young people, many of whom are being unfairly targeted and some brutalized and some even killed, are just like my son or just like your son – that this is our community and this pain is felt by everybody. I think that is the real impetus of the Black Lives Matter movement. A lot of people wrenched it out of context with the reply ‘All Lives Matter’ – I mean, that's self-evident. Of course, all lives matter but all lives had not been brutally treated in the way that these young black lives have. It was an effort to stand up and wave a hand and say, ‘hey, we matter too. We are part of these communities. Treat us like human beings, let alone citizens, but treat us like human beings.’ That's what the movement was about and young people need to continue that effort.

Do you think it risks being quashed during this new administration? When you see the public protests around the immigration ban, does it give you hope? What happens next?

I think it is at risk of being criminalized, because President Trump has said he's going to be the law and order president and he made some very negative comments about the protests. But if the recent Women's March and the march in support of immigrant families is any indication, I think that if nothing else this election has awakened people. Emerson once said, ‘Our democracy was in danger of sleeping.’ Not so much anymore. I think people are awake and they're going to stay awake and stay engaged and I think that's a good thing.

As a leading thinker in the judicial center, how do you process Jeff Sessions as Attorney General?

I'm deeply concerned about General Sessions. I remain deeply concerned about that appointment. As a general matter and as a default principal, I think that elections have consequences and that presidents have a right to appoint their senior most staff, including Attorney General and so forth. We may not like their policies but, again, that's what the democracy is all about.

So, I don't make the following claim lightly when I say that were I a senator, I would have voted against General Sessions, and the main reason is his record on civil rights litigation. There was a case called the Perry County Three when he was US Attorney in Alabama, and this was thirty years ago but it speaks volumes. In the Perry County Three, there were three African American activists who went into the community and attempted to educate people in what was called the Black Belt, where a lot of black people lived. They had been disenfranchised and had never really voted before. They got that community registered and advised them on how to go to the polls and vote, and educated them on what issues were important to their community and so forth, and then US Attorney Sessions prosecuted them under a federal law.

The judge in the case, a conservative judge, on the record said that he didn't buy any of these theories that Sessions used to continue the case, but Sessions persisted nonetheless. Voting is the most basic of our civic rights and to criminalize someone for attempting to aid and assist someone in voting is repugnant to the very ideals for which this country stands.

Actually, our former governor, Deval Patrick, was a very young NAACP Legal Defense Fund lawyer who represented one of the Perry County Three down in Alabama. They were vindicated. They were found not guilty on all charges.

The other thing that Sessions did as United States Attorney was he aggressively investigated the absentee ballot fraud, and at first blush one might say, ‘Okay, that's fine. People shouldn't fraudulently use absentee ballots,’ but it was his selective investigation of it. He only investigated African Americans who submitted absentee ballots and then only in those districts where white incumbents were at risk, and that's deeply problematic.

We do these hearings ostensibly because they're proxies for how someone's going to behave. With this data of how he has behaved when he was the senior law enforcement official in that district in Alabama, it seems to me a pretty strong proxy for how he may behave as Attorney General, and if we don't have an Attorney General who is committed to the most basic of all our rights – the right to vote – then I think that's problematic and I am troubled by that confirmation.

There's almost no diversity in Trump's cabinet. Of 22 people: one is black, four are women, one is Hispanic and one is Asian. His inner circle and those without confirmation are all white males except for Conway, for whom I admit I have my own bias — How can people work around this reality of dismal diversity surrounding President Trump.

That's a great question. I had eight years of access to the White House. I don't know what happened. It just went away. I have no clue what to do anymore. (Laughs)

Do you expect states with more diverse populations to step up?

Yes, at state and local levels, that's where the battlegrounds are and you have to start at the local level and allow it to percolate its way up. The current administration won the election and they operate the government. His nominees will be confirmed and they will imprint his policies.

If people object to that optic, then they have to make sure that there's a different optic at their local and county and state governments and then in four more years we have another election.

What is the Jamestown Project you founded here in Cambridge?

The Jamestown Project that I and a group of others founded is a think tank that focuses on notions of domestic democracy and how we get a more robust participatory democracy. It brings together scholars, activists, and policy people to get in a room and figure out ways to engage the democracy. We meet at least once a year, but with computers and the ten or so fellows and staff, we are really in constant contact.

What's the current mission?

Our mission always has been working to achieve our democracy. Our view is that the democracy is always evolving and that if we think we've got it right, then we've got a problem. This democracy is something we should always be working towards – some things we always should be massaging and attempting to make better.

We think now is an ideal time for citizens to band together and make sure that we continue to achieve our democracy.

What public opinion would you like to change?

That's a deep question. I hope this doesn't feel redundant but I would want to change the unfortunate pervasive opinion that young black maleness equates in some way with criminality and I think that opinion motivates so much, unfortunately.

You were here at Harvard Law as a classmate of Obama and Supreme Court nominee Gorsuch. Was it obvious back then that these classmates would emerge as leading figures in American policy. What did that classroom look like?

They were older than me. I knew President Obama when I was in law school. I was a first year during their third year. I did not know or at least I can't remember Judge Gorsuch. That would've been an interesting comparison. I do remember Senator Cruz who was a few years behind me as a young student and, yes, you absolutely knew he was going to be a very successful politician. I have been wracking my brains to think if I interacted with Judge Gorsuch but again I would've been a fledgling One L when those guys as Three L's were in the hallways.

What was President Obama like as a classmate?

He was great. He was a mentor. People always ask me, ‘give me insight into his personality. What sort of quirky things did he do?’ and in those days, most people went straight through from college to law school, as did I. The president had worked several years as a community organizer before he came back to law school. He was twenty-seven while the rest of us were twenty-two and while that's not a big gap now, it was a huge gap then. He always seemed so much more mature than the rest of us.

Was he already statesman-like? Did he give off that vibe?

That's right. He had worked already and nothing matures you like having to pay your own rent. He would always seem steady as a rock. Now he will probably have a revisionist memory of this but I do have clear memories of utter dominance: me dominating his team on the basketball court.

You dominating the basketball court?

Absolutely. Absolutely. That's my clear memory of those days.

Where do you relax?

My library. I have a library in my home that's full of dusty old books and I can I sit there and nestle up with some old dead writer and that really provides a sense of stillness for me, which I very much need. It rejuvenates me.

Would you offer us a few book recommendations, Professor?

One would be Richard Rorty's Contingency, Irony and Solidarity. I think people will find it just a beautiful read and one way to help make sense of this crazy world in which we live. Michelle Alexander wrote a wonderful, wonderful book called The New Jim Crow. Baldwin's The Fire Next Time is one of my all time favorites and something that I read at least once a year. Anything by Dostoevsky - just a fabulous writer. I read at least two Dostoevsky novels a year, or reread, I should say. So, The Idiot is one of my favorites and, because I'm a criminalist, Crime and Punishment. I love it.

A BIG THANK YOU

When I set out to do these interviews, it was really to pull myself out of fiction and re-enter the world as a journalist. I would never have believed that I would still be publishing one of these interviews every 2 weeks, 4 years and 100 interviews later. There are so many people who make TheEditorial.com work. I hope you will look at our About page and see my right-hands: transcriber Mike Trupiano who jet-sets between Berlin and Brooklyn listening to these full interviews and transcribing them to perfection and copy editor Hannah Risser-Sperry who left Boston for Portlandia and stays with us. These two have touched almost every single one of these interviews. And Conrad Warre, contacted me in our first year to offer to help understand social media and has stuck with us all the way through. Thank you, Conrad. Contributors who helped us build a more dynamic and inclusive collective were journalists Sarah Baker and Jaime Kaiser and filmmaker David Cripton – each of them brought editorial voice to the 100 interviews and helped us to shape our dialogue.

Our photography made these interviews sing!! and I am indebted to the many photographers who carry these interviews with me: beginning with the highest bar set by the uber-talented Susan Lapides who helped form our early visual footprint, and furthered by a long list of photographers including Alan Savenor, Kira Hower, Eric Levin, Melora Balson, Chehalis Hegner and Grace Kwon. Without this team of people, we would never have reached this milestone of sharing for free the incredible ideas whirling along this MIT, Harvard, Cambridge and Boston corridor. Along the way Jared Steinmark helped us redesign, Tara Keppler designed our logo, single print issue and posters that are like work of art that hung for two years at the Kendall Square Association and now hang in the Cambridge Public Library, Marcie Campbell helped us pull off some of our most successful live events, and Sharon French continues to be the ultimate sounding board and sage. I have sat with so many of you to think through how we can grow, contribute to this world and collaborate like Cristina Blau, Tim Hawk, Rebecca Walsh and Jill Forney, to name a few. Because we are an independent media company and a startup (terrible combination for early funding!), all of these people are doing this more out of passion than earning because, trust me, the pay is dismal. We keep hoping someone will help us grow and fund an even bigger initiative and I will always remember the time, talent and creativity that this team gave to building and creating Version 1.0. Thank all of you for reading and for telling others about us and sharing our interviews. We did it!